Written By

Department of African American Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University

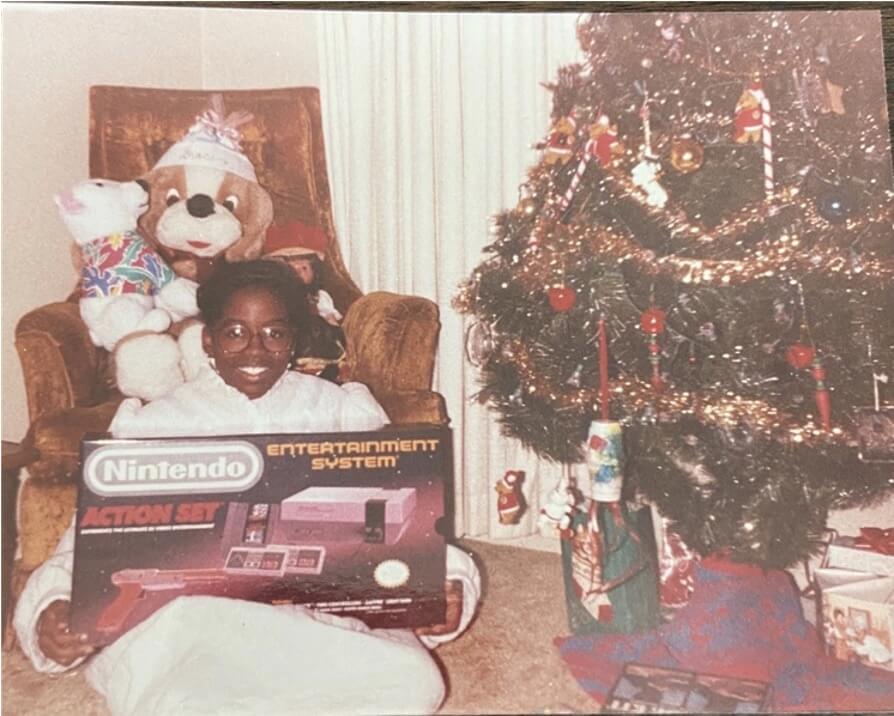

It was Christmas 1986, one of the happiest days in my childhood. It was the year I received my very own Nintendo gaming system. One of the very first ones that included Super Mario Bros. and Duck Hunt games along with the controllers and NES Zapper. This shades of gray and black with red letters gaming system was the equivalent of winning the lottery for a five-year Black girl…I was on top of the world (Figure 1)! Some years later I would also get Nintendo’s 8-bit handheld game console, “The Game Boy” and play Tetris until I exhausted all of the levels. These early gaming moments were filled with child-like innocence and without fear. During these moments, I was not thinking about exclusion and diversity, it was all about how I can get more playing time (or in today’s terms screen time) with new gaming toys. Gaming was an opportunity to escape the household chores for that week, something to look forward to after finishing my homework, or a supplement to Saturday morning cartoons.

While I am not as active of a player as I was growing up, I’ve switched gears from escaping to play video games to examining the gaming industries global media impact. Since the 1980s and 1990s the gaming industry has evolved to include more elaborate storylines and graphics, new modes of communicating with other fellow gamers, and see the first HBCU (Benedict College-located in Columbia, South Carolina) [For more information see here] to host an Esports competition along with establishing an undergraduate degree, minor, and certifications. To say I am amazed is an understatement. Even in my amazement, there is still work to do to normalize the Black experience in gaming.

Fast forward to February 2012 the world must process the murder of Trayvon Martin, in March 2020 the killing of Breonna Taylor, and the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue in Richmond, VA. As a result of the aforesaid events, which encompass police violence, white supremacy, and systemic racism, numerous protests took place nationally and globally. While the world was grappling with the continuous violation of Black bodies, there would also be a ripple effect taking place in the gaming industry. Several gaming companies like Electronic Arts, Epic Games, Riot Games, and Sony Interactive Entertainment/PlayStation took forward steps to publish statements of their support (Entertainment Software Association, n.d.) as well as make financial contributions to numerous advocacy organizations (i.e. NAACP, National Urban League, Black Girls Code, Black Lives Matter). Many of these organizations seek to achieve Black freedom/liberation, change in policy/policy reform, direct action, and improve community relations (locally, nationally, and globally).

These same thoughts can and do translate into the gaming space, more specifically through its Black gamers/players. As argued by software analyst Jordan Minor in a 2020 PC Magazine article, “Video games aren’t special. They exist in the same world as everything else and are impacted by the same social, cultural, and political forces.” Thus, gaming has much work to do as it relates to diversity and the acknowledgment of equitable representation. More specifically, when discussing video game character development, the default has historically been cis-, white and male. This becomes problematic when users try to identify with the characters they are playing (Williams et al., 2009). Hence, many Black players and even creators take on a position of suffering in silence, alienation, and a need to belong. Yet, the gaming space, as argued by Kishonna L. Gray, does have the potential to explore the “treacherous terrain” that many Black players experience (Gray, 2020). Furthermore, the essay offers an examination and imagining of the gaming space through an Afrofuturistic lens and how it creates discussions around the relationships between race, access, and technology (Nelson 2002) while also figuring out ways to close the gaming/digital gap. However, before exploring why and how #BlackGamersMatter in this “treacherous terrain” it is necessary to offer some background into the larger relationship between Blackness, technology, and gaming.

In today’s society, technology touches every facet of our lives, whether we are sending an email, playing “Words with Friends” or “Wordle”, catching up on the latest Tik Tok video or Black Twitter update, tuning into the Webby award-winning podcast Jemele Hill is Unbothered or gearing up to play the Ubisoft game, “Watch Dogs 2.” As noted by Black studies and technology scholar Terrance Wooten, “we are currently living in a context wherein our encounters with various technological tools have increased in order to perform basic tasks” (Logan 2020). A clear example of this is with the daily use of Zoom, as it has become routine in the classroom, job interviews, and work meetings. However, when Blackness is inserted into the equation, the use of technology has historical roots fraught with inequities, exploitation, and uninvited surveillance. Representations of anti-Blackness and racist experiences suffered by Black people are not always restricted to offline settings. It has been argued that “race matters no less in cyberspace than it does in ‘IRL’ (in real life)” (Kolko, Nakamura, and Rodman, 2013) and that Black bodies and their experiences (much like in the gaming space) must be protected from white fears and anxiety if they are to be a part of the future. The protection of our digital Black presence is ultimately about protecting Black futures and correcting past actions (Johnson and Neal 2017). This future-forward protection has been particularly taken up in the academic world as the conversations incorporate the many nuances of Black people’s technological experiences.

In the last 10-15 years, there have been many notable Black scholars making huge strides when discussing, researching, and interrogating the existence and relationship between Blackness and technology. The digital code and blueprint are being redrawn from white surveillance and scholars are finding ways to regain a sense of humanity which has been historically stripped from Black people. Some of the earliest scholars who engage with the layered relationships between technology and Blackness specifically through social media, digital analytics, and the representation of marginalized communities in media includes Safiya Umoja Noble’s work on the relationship between search engines and discriminatory practices through her groundbreaking 2018 text Algorithms of Oppression. Noble’s work in Algorithms of Oppression is specifically examining how algorithms can and do replicate and reinforce racist and sexist beliefs, which become embedded in society. André L. Brock (2012) explores the many layers of Twitter as a cultural conversation, particularly the way in which Black Twitter serves as a cultural outlet and “social public.” Noble and Brock’s work is significant considering many Black gamers and gaming commnities heavily rely on social media usage (particular Twitter and TikTok) as a way to promote participatory engagement and alternative community building.

We are also seeing examinations of Black women and social/digital capital, the relationship between whiteness, Blackness and digital technoculture (Brock 2020). Both Noble and Brock further the conversations around the future of public knowledge, information culture, and how culture shapes online social interactions. Additionally, Catherine Knight Steele’s work on creating spaces of community within online spaces, and the layered dynamics between race, gender, and media furthers this conversation through her 2021 book Digital Black Feminism. Using the concept of a virtual beauty shop as a metaphor, Steele takes a deep dive into exploring the relationship between technology and Black feminist thought, while offering insight into Black women’s complex and layered relationship with technology and the importance of centering their voices. Steele’s virtual beauty shop concept can also translate into the growing Black women and girl communities that are emerging in not just players of the games, but game creators.

Also, there are scholars who are researching the roles of digital activism, social justice, and digital knowledge production. These discussions are happening through the work of Ruha Benjamin and her examination of race and technology through the lens of innovation and social equity with such texts as: Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want (2022) and Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (2019); Sharon Tettegah (2016) who engages with the intersections between STEM, psychology and education as it relates to students of color; and Charlton Mcllwain’s (2019) work on technology and racism and the role of the internet and racial justice through his book Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter. As noted by Ruha Benjamin, Black intellectual tradition has always questioned modernity, and now there is an incorporation of technology (Princeton University, 2020). Thus, each of these scholars are breaking the codes and adding to the larger conversation of Blackness and technology as a tool to access freedom and gain political and social mobility. Much of these are earlier, reconsidered, or continued discussions and conversations around racial and gender equity, systemic and technological racism, and Black Lives Matter.

Additionally, there are several scholars who are specifically engaging in the work of Blackness and gaming, which includes Kishonna L. Gray’s (2020) work on the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and (dis)ability through her book Intersectional Tech: Black Users in Digital Gaming; and Lindsey Grace’s work on the creative contributions of Black game makers/designers/developers, designing social impact games, and future gaming archives through his books Black Game Studies: An Introduction to the games, game makers and scholarship of the African Diaspora (2021) and Doing Things with Games: Social Impact Through Play (2019). Both Gray and Grace address the biases in video game designing and developing, while simultaneously finding solutions. These efforts have long-term effects as they play a role in empowering marginalized communities, highlighting how virtual worlds can affect real-world networks and communities, and creating digital archives particularly for game historians, academics and hobbyists. By incorporating personal narratives and experiences from players and makers, it provides exposure and visibility and demonstrates that these are not isolated, solitary experiences.

As a growing topic that is being investigated from numerous disciplines including Africana studies, anthropology, communication studies, gender/women/sexuality studies, library and information studies, new media studies, and sociology, the study of Blackness and technology has made a significant mark within academic circles. In addition to the above-mentioned scholars and their important texts surrounding Blackness and technology, there have been other ground-breaking compilations such as the “Black Code” 2017 special issue of The Black Scholar (Johnson and Neal, 2017); The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online (Noble and Tynes, 2016); and solo texts like Feminista Jones’s (2019) Reclaiming Our Space: How Black Feminists are Changing the World from the Tweets to the Streets; Mar Hicks’s (2018) Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing; and Sarah Florini’s (2019) Beyond Hashtags: Racial Politics and Black Digital Networks. Most, if not at all center Blackness across a range of themes and platforms, while highlighting the joys of being online and the intersections of Black freedom struggles with Black play and praxis (Johnson and Neal, 2017). As scholars continue to push the boundaries and margins of the digital landscape, reshape the beliefs and expectations of who belongs in the room or behind the control, and confront the systemic violence, there is hope that future possibilities between Blackness and technology are endless.

“Video games are not just games or sites of stereotypes, but a space to engage American discourses, ideologies, racial dynamics” (Leonard 2003).

The above quote speaks to a long-standing sentiment that specifically addresses the gaming world, in particular video games, but can also speak to society’s engagement or lack thereof with Black people. As a $100 billion enterprise, one that financially surpasses the film and music industry, and a global gaming audience of 2.6 billion, one might ask how and where does the representation of Blackness factor. Even the conversations around diversity, equity, and inclusion are not immune to the gaming industry. This was made very clear particularly during the summer of 2020, when there was an increase of content creators, publishers, and video game studios coming to the forefront for justice after the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer. Much of these efforts to show solidarity and allyship were conveyed through various tweets:

Playstation denouncing “systemic racism and violence against the Black community” (Figure 2):

— PlayStation (@PlayStation) June 1, 2020

Insomniac Games “donating to national and local organizations” and expressing their dedication “to making a positive and lasting influence on people’s lives.” (Figure 3):

— Insomniac Games (@insomniacgames) June 1, 2020

Ubisoft making specific contributions of “$100,000 to the NAACP and Black Lives Matter.” (Figure 4):

We stand in solidarity with Black team members, players, and the Black community. We are making a $100,000 contribution to the NAACP and Black Lives Matter and encourage those who are able to, to donate. #BlackLivesMatter pic.twitter.com/KpHZCF6VWx

— Ubisoft (@Ubisoft) June 2, 2020

And a specific charge from Call of Duty: Modern Warfare developer Infinity Ward to addressing and combatting racist content from its players (Figure 5):

— Infinity Ward (@InfinityWard) June 3, 2020

However, the murder of George Floyd would not be the only occurrence that led to public frustrations, outcries, concerns, and action. While many of the challenges speak to the limited representation as well as racist and sexist content of video games, there are also growing internal labor challenges. In July 2020 allegations of widespread sexual misconduct/gender discrimination were made against Ubisoft (a major player in the gaming industry) from its employees, which caused three top executives to resign. Following those events, a year later in July 2021 a California lawsuit was also brought against Activision Blizzard for sexual harassment and discrimination among its employees. There has been a consistent history of gamers, indie developers, and industry veterans of color who have steadily demanded for tenable solutions that speak to the gaps and inequities within the gaming field. This is also reflected in a 2022 Games Developer Conference survey, where almost a quarter of the developers said their studios had not focused any resources on diversity or inclusion initiatives within the last year. Much of this is attributed to internal biases, recruitment, and outreach efforts. While changes and efforts are gradually happening, they must happen on a consistent and effective basis. Allowing racist, sexist/misogynistic ideas and misconduct to be normalized and go unchecked, ignoring opportunities to increase representation, and operating in a reactive versus proactive mindset can have lasting repercussions and lingering trauma. As society continues to evolve it is essential that these changes take place in all aspects of life, even in the popular gaming world. Considering the amount of increased visibility that gaming is getting, especially within marginalized communities, it is necessary that we move from making the demands for change to actually facilitating the changes.

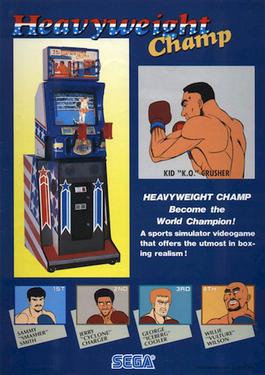

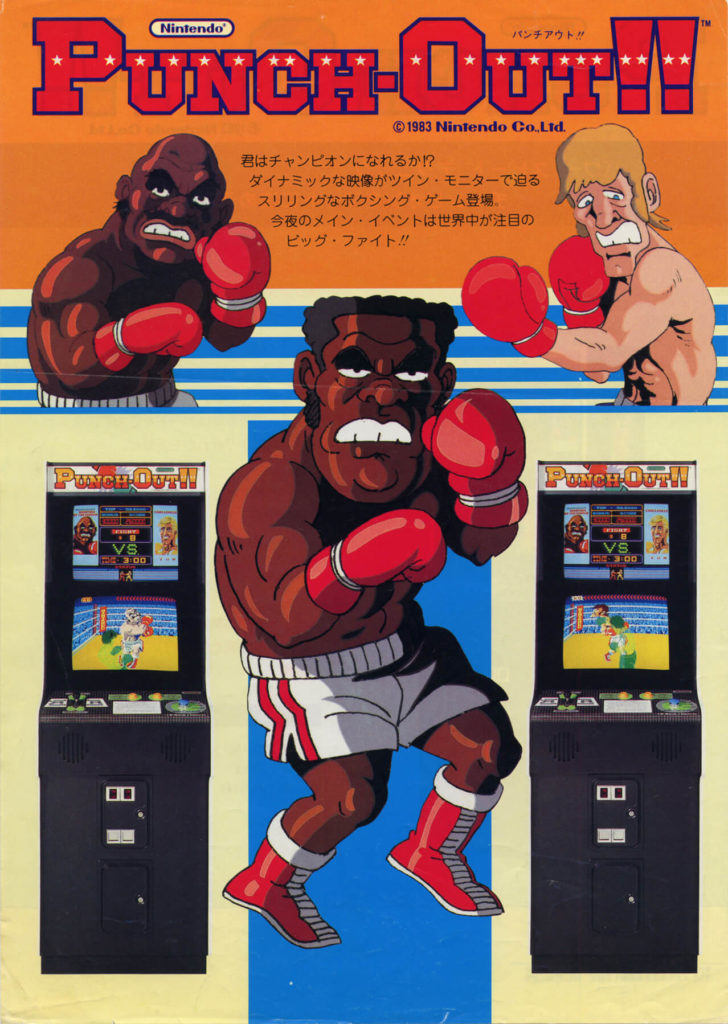

Much like how history, dictated through a white lens, has created a narrative that Blackness/Black people have a limited existence within popular culture or specifically that we do not exist in science fiction, fantasy, speculative fiction realms, this myth is very much present throughout the gaming arena. The first video game featuring a Black person was the SEGA game “Heavyweight Champ” (Figure 6) an arcade game released in 1976, remade in 1987, and re-released in the early 1990s.

Early video game interpretations of Black characters were primarily portrayed in sports and fighting games (i.e. “Heavyweight Champ” and “Punchout” [Figure 7]) or as problematic caricatures with Blackface, exaggerated and grotesque features.

An example of this characterization can be found in the role-playing video game “Square’s Tom Sawyer”1 (Figure 8). When specifically engaging with the larger character picture, as noted by digital media scholars Anna Everett and S. Craig Watkins (2008), nearly 70% of video game protagonists are White males, while communications scholars Dmitri Williams, Nicole Martins, Mia Consalvo, and James D. Ivory (2009) stretch that figure to nearly 80%. Between the two studies, each discovered that even with the increase of Black and brown bodies represented in actual video games, the depictions are limited to criminals, hustlers, hyper-violent terrorists, athletes, and brawn over brain sidekicks.

Of these characters, even fewer are Black women, who are often portrayed as ambiguously presenting, hypersexualized vixens, or simply just background roles. Other issues that Black female players deal with include character aesthetics. Until recently, Black hairstyles (i.e., locs, afros, braids, kinky curls) were infrequently seen in mainstream video game designs and were represented under western, European beauty standards. Unfortunately, these characters and their corresponding narratives barely get any screen time and suffer from overexposure or lack of character complexity. In spite of these misrepresentations, there have been independent gaming companies such as game developer Ian Sundstrom’s Sundstrom’s Herringbone Games who are diversifying their characters in real-time. Through the creation of his tower-building game “Stacks on Stacks (on Stacks),” Sundstrom’s main protagonist is a young, Black girl with varying natural hairstyles (e.g., kinky and curly, mini afros, and two pigtails), Rockit, who has the ability to fly like a rocket. This is an example of normalizing representations of Black female characters, introducing natural hairstyles, and also an invitation to discuss Black girls in STEM.

Still, even with positive strides, Black gaming consumers, producers, and characters continue to have a strained relationship. While the gaming industry is largely dominated by white men, Black and brown voices have a growing presence. In a 2015 study from the Pew Research Center’s Teen Relationship Survey showed that 83% of non-Hispanic/Black teenagers play video games, compared to 71% of Caucasian teenagers, with 69% of Hispanic/Latinx teens not too far behind (Lenhard 2020). This is important to note as the numbers show high percentages of Black and brown teens playing games, but unfortunately these same numbers do not reflect the same character representations within the games that are being played. When considering the actual staffing/game developers, another report from the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) notes among game developers worldwide 81% identify as white/Caucasian/European, 7% identify as Hispanic/Latinx, and 2% identify as “Black/African-American/African/ Afro-Caribbean” (Westar, Kwan, and Kumar, 2019). What is also important to note is the lack of diversity on the game creation side. Tanya DePass, founder of the nonprofit I Need Diverse Games, argues that for companies that are invested in improving diversity in their content, “the biggest thing is diverse staff, and diverse staff at the leadership level” (Peckham 2020). Furthermore, in order to make this a reality, game studios must hire outside consultants and experts that can review their development plans, while simultaneously providing feedback on where their content may include stereotypes or misrepresent an ethnic group. DePass further argues that a proactive approach is necessary, thus, diversity consultants “should be present in the beginning, not a month before launch” and the action must be treated seriously (Peckham 2020). In addition to the above-mentioned recommendations, Black and brown creators and developers are also no longer simply relying on acceptance into abusive and toxic companies and corporations. As the video game industry increases as a global phenomenon and evolves, the work still continues. This work is coming to fruition through the creation of Black gamer communities.

“When Black women claim space it changes the world” (Michael, 2018).

Even in the midst of sparse beginnings, Blackness and gaming has always and will continue to have a unique and complex relationship. Through much resistance and constant action, it is essential that the Black gaming experience moves from not just surviving and existing but also thriving. As a way of “playing the game” through community building at the core of this play is something quite simple… finding joy. Although many Black gamers, creators/designers, and consumers of the video game industry are often bothered, frustrated, harassed, and pushed to the margins due to racial stereotypes, gender disparity, and inequitable access, there is still a feeling of hope and a will to change the script and narrative. These running issues are in the constant rearview for Black women. Finding communal safe spaces to belong and have fun in the process, is a constant game—literal and imagined—that Black women and girls return to even when they are constantly on the verge of seeing the infamous phrase/message no player wants to see, “Game Over.” However, even with dodging this phrase Black women have maintained a legacy of resilience particularly in the gaming world. As noted in the above quote by musician Michael Love Michael (2018), Black women are continuously occupying the spaces they encounter and making major developments. Considering Black women have had a complicated relationship with science and technology (i.e. forced sterilization, medical experimentation, lack of inclusion within STEM programs), oppression and marginalization within gaming is no exception. Black women are course-correcting this relationship vis-à-vis the narratives told through gaming.

Turning Visions Into Imagined Realities. Black women are moving beyond being seen as sideline and/or fetishized characters and “unicorn gamers” and are instead carving their own lanes in this growing popular culture market. As stated by the late novelist Toni Morrison, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” This same notion applies to the gaming industry, specifically Black and brown women gamers as they have taken up this call and created their own playing field. One of the first communities created for female gamers, Sugar Gamers, was founded in 2009 by a South-side Chicago based gamer and entrepreneur Keisha Howard. Like many gamers, Howard was on a mission to connect with other like-minded women gamers who had similar interests and ideas. From the onset, Howard wanted to create a community for female gamers to feel like they have a voice and acknowledge their presence. Yet, now the platform has an even larger purpose of welcoming all marginalized and underrepresented voices as well as creating opportunities for growth and change.

One place where this growth and change has occurred is through an open-source multimedia experience called Project Violacea. Defined as an on-going project, Project Violacea is “a vision of the future that serves as a setting for various creative works by the Sugar Gamers, such as games, fiction stories, art, movies, and comic books” (Tonge, 2019). This has become a real-time version of Afrofuturism in action as it incorporates genres such as science-fiction, speculative fiction, and eco-feminism, while addressing such concerns as climate change, sustainability, global pandemics, surveillance, and gaining freedom. As an active project, members of Sugar Gamers are able to design their own personal characters, write and create corresponding backstories, and cosplay as their characters. Additionally, members can contribute to the nationwide #CreateNotComplain crowd-sourcing campaign. According to the Sugar Gamers community, Project Violacea is a next level step not just for advocacy but also a “functional demonstration of the power of diversity in action” (Tonge, 2019). As a multi-media vision, Sugar Gamer members are using this fictional media format to re-write, re-tell, and reclaim a narrative that has been distorted and build a future where they see themselves safely playing.

In addition to multimedia projects, Sugar Gamers serves as a community platform that is a regular source for tech and gaming news. Some of their posts also include topics on Rihanna’s Fenty Beauty cosmetic line partnering with Riot Games (Tonge, 2022), IKEA’s new gaming collection (Jefferson, 2021), and “Hip-Hop Gamer” Gerard Williams (Nina, 2021). All in all, Sugar Gamers prides itself through a core set of values: diversity, inclusion, and fresh perspectives. These values speak to a long-term game plan that is looking toward the future. While Sugar Gamers began as a space for women’s advocacy and professional and consumer networking, it ultimately became an organization that informs, educates, creates experiences through live extended reality (XR) learning tools,2 and facilitates professional development through their internship program. As an organization it embodies what it means to be recognized and acknowledged in the present and continue to exist in the future.

What’s in a Hashtag? Operating in the same vein as Sugar Gamers is the online platform, I Need Diverse Games (INDG). This project was born out of a reactionary tweet (#INeedDiverseGames) in response to the lack of diverse protagonists being featured in the latest list of upcoming games.3 Created in 2014 as a non-profit foundation, DePass and INDG have been dedicated to aiding underrepresented people gain access and visibility within the gaming industry, while also offering scholarship/financial assistance through travel/housing grants and passes for game developer conferences and conventions. These efforts have allowed the opportunity for 25 scholar participants to attend the annual Game Developers Conference4 with an all-access pass (valued at $1600) each year since 2015-16. Moreover, through her foundation and own personal passion, DePass who also identifies as a gamer (her handle on Twitch5 is ‘Cypheroftyr’), seeks to change the narrative of who is in the room and sitting at the table. DePass argues, “If we’re not in the room, we don’t have a way to bring up these issues without worrying about being the squeaky wheel and losing the job that a lot of us need… it’s not just getting in the room; it’s getting in the room and being heard and having your ideas treated respectfully” (Thompson, 2022). Over time, DePass has become hopeful that changes are happening and that gaming is evolving. Tracking the data for INDG from the International Game Developers Association (IGDA), she found that less than 1% of all respondents identified as Black and less than 4% identified as Asian (Weststar et al., 2021).6 Ultimately, INDG seeks to discuss, analyze, and critique identity and culture in video games through a multi-faceted lens rooted in intersectionality.

“We’re energized by the opportunity to change the way people think about gaming” (Black Girl Gamers).

The above quote can be read as a call to action for gamers in the present and hopeful future. As the first thing that viewers see when entering their website, Black Girl Gamers is making a bold statement and establishing who they are as a gaming community. Defined as an “inclusive online gaming community,” Black Girl Gamers is one of the most successful and largest gaming communities for Black women, amassing over 8,000 members worldwide. Black Girl Gamers was founded in 2015 by British author and blogger, Jay-Ann Lopez, as a Facebook group providing community for Black women gamers (Lopez, 2015). In the under 10 years that it has existed, Black Girl Gamers has made a global impact and created partnerships with such organizations as Google, Playstation, Twitch, Riot Games, Adidas, Facebook, EA, and Netflix. Much like the above-mentioned organizations, Black Girl Gamers also prides itself on diversity, inclusion, and equity for Black women in gaming.

Motivated to change the gaming landscape from impersonators and opportunists of Black culture, Lopez redefines what it means to “play the game.” As a global business community, Black Girl Gamers has been able to produce regular media content, assisting with brokering and securing talent through “BGG Talent,” and establish online and offline events such as their Twitch-sponsored Black Girl Gamers Online Summit, “IRL Pass the Pad,” and an array of brand store takeovers. Since the gaming community, as a whole, consists of consumers and producers, Black Girl Gamers takes an active role in not only advocating for Black women gamers, but also creating long-term opportunities. Much like the way Afrofuturism is a valuable tool for healing and “wielding the imagination for personal change and societal growth” (Womack, 2013), Lopez and her Black Girl Gamers team are empowering Black women to see themselves as innovators and free thinkers in an online safe space. Bringing in a Black femininst energy to the gaming space, the members through the various events, workshops, and partnerships can establish their own standards and lens through which they view the gaming world and the way the gaming world views them (Womack, 2013, p. 104). Operating from an unapologetic manner, Black Girl Gamers are free from having to wear a mask that disguises who they really are or having to code switch to make others feel comfortable.

The above communities were selected based on each being created specifically by Black women and how they are shifting the gaming paradigm, and in turn they are reclaiming space that has been previously denied to the Black female gaming community. Operating on their own terms, each of these organizations exemplify what I call a breakthrough vision. They have made their mark in an industry that has overlooked their potential and value, while implementing and executing various visions that reach the masses.7 Digital culture and game studies scholar Frans Mäyrä (2008) suggests that gamers who come together to play possess a shared language, while simultaneously engaging in collective rituals. The collective language and rituals offer a space to generate solutions, build relationships, and even share resources. Taking on attributes of self-determination, visualizing alternate realities and futures becomes a way to channel a language of resilience, which is familiar territory for the survival of Black women. Sugar Gamers, I Need Diverse Games, and Black Girl Gamers function as intersectional communities and platforms that disrupt hegemonic narratives (Gray 2020) by designing multiple lanes of visibility, commanding attention and access, and illustrating that Black women do belong in the gaming world. Ultimately, through each community they have escaped alienation, imagining futures from forgotten pasts, and establishing new gaming traditions.

Video game culture has always been about passion, desire, and creating stories through various environments (i.e. fantasy, reality, sports, city planning). While gaming companies are still struggling to hire and maintain Black staff there is still a high degree of hope that gaming will move away from it being solely synonymous with cis-, white, and male. With the rise of Black gaming communities and their participation in forums, conventions, and camps, they also are taking an active role to improve connections and build support between gamers and the video game industry while highlighting issues that are important to them. As these voices continue to speak on the long-standing intersectional issues of racism, sexism, and homophobia, it will not be as easy to be passive, or worse, blatantly ignore them.

As someone who identifies as a Black Future Feminist with an interest in comics and gaming it is important to see myself and create new lines of intellectual inquiry with voices that are often marginalized and/or made invisible. Black gamers, creators, and developers will always continue to take up space, challenge the system, and demonstrate the power of inventive re-imagination. Furthermore, I am very hopeful and excited about what the future holds for Black gamers. Reflecting back on my childhood as a young, naïve, precocious gamer I did not understand the lack of visibility and Blackness in the gaming world. I would not begin to comprehend or even imagine the transformation that is currently happening in this billion-dollar industry. Yet, while I am fully aware of the necessary need to rewrite and reclaim the script of Blackness and gaming, a part of me still reflects back to Christmas 1986, where I just simply wanted to play my Nintendo and have fun.

(presented April 2022, published May 2023)

1 In 2010, Unified Gamers Online ranked the game as #4 most racist video game in history (Dashevsky, 2017).

2 XR/Extended Reality is a universal term that includes such immersive technologies as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR) which create simulated learning environments where participants complete [realistic] interactions with people and objects.

3 This same viral response can be seen through #Afrofuturism (see Gipson, Grace D. “Creating and Imagining Black Futures through Afrofuturism.” In #Identity: Hashtagging Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Nation, edited by Abigail DeKosnik and Keith Feldman, 84-103. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019.).

4 The Game Developers Conference is a “premiere professional event” where participants come to “exchange ideas, solve problems, and shape the future of the industry”. This is done through education, networking, virtual workshops, and hands-on training. Attendees of GDC include programmers, artists, producers, game designers, audio professionals, and business leaders (https://gdconf.com/about).

5 Twitch is a video live streaming service that focuses on video game live streaming, broadcasts of esports competitions, music broadcasts, and a space for creating ‘real time’ content.

6 Those numbers have risen to 4% and 7%, respectively.

7 Additional communities and forums centered around Black and brown women that are promoting like-minded media content, safe spaces to play and create, networking and opportunities to share their love and passion for gaming and technology include: Thumbstick Mafia, Brown Girl Gamer Code (BGGC), and The Black Simmer.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge: Polity Press. 2019.

Benjamin, Ruha. Viral Justice: How We Grow the World We Want. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Forthcoming 2022.

Brock, André. “From the Blackhand Side: Twitter as a Cultural Conversation.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 56, no. 4 (2012), 529-549. doi:10.1080/08838151.2012.732147.

Brock, André L. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. New York: NYU Press, 2020.

Dashevsky, Evan. “18 Bizarre Video Game Adaptations That Actually Exist.” PC Magazine, February 4, 2017. https://www.pcmag.com/news/18-bizarre-video-game-adaptations-that-actually-exist.

Entertainment Software Association. “Video Game Industry Response to Nationwide Protests.” Entertainment Software Association. Last modified June 2, 2020. https://www.theesa.com/news/video-game-industry-response-to-nationwide-protests/.

Everett, Anna, and S. Craig Watkins. “The Power of Play: The Portrayal and Performance of Race in Video Games.” In The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning, edited by Katie Salen. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Florini, Sarah. Beyond Hashtags: Racial Politics and Black Digital Networks. New York: NYU Press. 2019.

Games Developer Conference. “State of the Game Industry 2022.” Games Developer Conference, informatech, Mar. 2022, http://www.reg.gdconf.com/state-of-game-industry-2022.

Gipson, Grace D. “Creating and Imagining Black Futures through Afrofuturism.” In #Identity: Hashtagging Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Nation, edited by Abigail DeKosnik and Keith Feldman, 84-103. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Grace, Lindsay D. Doing Things with Games: Social Impact Through Play. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. 2019.

Grace, Lindsay D. Black Game Studies: An Introduction to the games, game makers and scholarship of the African Diaspora. Pittsburgh: Carnegie Mellon University ETC Press. 2021.

Gray, Kishonna L. Intersectional Tech: Black Users in Digital Gaming. LSU Press, 2020.

Hicks, Mar. Programmed Inequality: How Britain Discarded Women Technologists and Lost Its Edge in Computing. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2018.

Jefferson, Katrina. “Ikea’s New Gaming Collection With Republic of Gamers Gives Us Yet Another Reason To Pull Up.” Sugar Gamers (blog). September 24, 2021. https://sugargamers.com/ikeas-new-gaming-collection-with-republic-of-gamers-gives-us-yet-another-reason-to-pull-up/.

Johnson, Jessica M., and Mark A. Neal. “Introduction: Wild Seed in the Machine.” The Black Scholar 47, no. 3 (2017), 1-2. doi:10.1080/00064246.2017.1329608.

Jones, Feminista. Reclaiming Our Space: How Black Feminists are Changing the World from the Tweets to the Streets. Boston: Beacon Press. 2019.

Kolko, Beth, Lisa Nakamura, and Gilbert Rodman. “Race in Cyberspace: An Introduction.” In Race in Cyberspace, 4. London: Routledge, 2013.

Lenhart, Amanda. Teens, Technology and Friendships. Pew Research Center, May 30, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/08/06/teens-technology-and-friendships/.

Leonard, David. ““Live in Your World, Play in Ours”: Race, Video Games, and Consuming the Other.” SIMILE: Studies In Media & Information Literacy Education 3, no. 4 (2003), 3.

Logan, Jim. “‘Anti-Blackness and Technology’.” The Current-UC Santa Barbara, November 17, 2020. https://www.news.ucsb.edu/2020/020098/anti-blackness-and-technology,

Lopez, Jay-Ann. “ABOUT.” Black Girl Gamers (blog). 2015. https://www.theblackgirlgamers.com/about.

McIlwain, Charlton D. Black Software: The Internet and Racial Justice, from the AfroNet to Black Lives Matter. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 2019.

Michael, Michael L. “4 Moments Black Women Took Up Space and Changed the World.” PAPER, July 6, 2018. https://www.papermag.com/black-women-taking-space-2584130216.html?rebelltitem=7#rebelltitem7.

Minor, Jordan. “Video Games Owe Black Players More Than Just Talk.” PC Magazine, June 18, 2020. https://www.pcmag.com/opinions/video-games-owe-black-players-more-than-just-talk.

Mäyrä, Frans. An Introduction to Game Studies. London: SAGE, 2008.

Nelson, Alondra. “Introduction.” Social Text 20, no. 2 (2002).

Nina. “An Interview with Gerard “Hip-HipGamer” Williams.” Sugar Gamers (blog). November 30, 2021. https://sugargamers.com/an-interview-with-gerard-hip-hipgamer-williams/.

Noble, Safiya U. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: NYU Press, 2018.

Noble, Safiya U. and Brendesha Tynes. The Intersectional Internet: Race, Sex, Class, and Culture Online. New York: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc. 2016.

Peckham, Eric. “Confronting racial bias in video games.” TechCrunch, June 21, 2020. https://techcrunch.com/2020/06/21/confronting-racial-bias-in-video-games/.

Princeton University. “Ruha Benjamin Discusses ‘Race After Technology’.” YouTube, 15 May 2020, http://www.youtu.be/rY8RkET3KC0.

Steele, Catherine K. Digital Black Feminism. New York: NYU Press, 2021.

Tettegah, Sharon. “Foreword.” Emotions, Technology, and Health, 2016, xi-xiv. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-801737-1.09999-6.

Thompson, Dillon. “I Need Diverse Games founder Tanya DePass on why the gaming industry needs diversity: ‘We’re simply not in the room’.” Yahoo. Last modified March 4, 2022. https://www.yahoo.com/lifestyle/twitch-streamer-tanya-depass-fighting-140000641.html

Tonge, Jennifer. “Project Violacea.” Sugar Gamers (blog). October 19, 2019. https://sugargamers.com/project-violacea/.

Tonge, Jennifer. “So…FENTY BEAUTY IS RIOT GAMES’ FIRST BEAUTY PARTNER NOW??” Sugar Gamers (blog). April 11, 2022. https://sugargamers.com/sofenty-beauty-is-riot-games-first-beauty-partner-now/.

Weststar, Johanna, Shruti Kumar, Trevor Coppins, Eva Kwan, and Ezgi Inceefe. Developer Satisfaction Survey-2021 Summary Report. International Game Developers Association, 2021. https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/18113901/IGDA-DSS-2021_SummaryReport_2021.pdf.

Weststar, Johanna, Eva Kwan, and Shruti Kumar. “Developer Satisfaction Survey-2019 Summary Report.” International Game Developers Association. Last modified 2019. https://igda-website.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/29093706/IGDA-DSS-2019_Summary-Report_Nov-20-2019.pdf.

Williams, Dmitri, Nicole Martins, Mia Consalvo, and James D. Ivory. “The virtual census: representations of gender, race and age in video games.” New Media & Society 11, no. 5 (2009), 815-834. doi:10.1177/1461444809105354.

Womack, Ytasha. “The Divine Feminine in Space.” In Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, 104. Lawrence Hill Books, 2013.

We welcome and encourage your comments. You must create a free account to participate.