Written By

“The Third Library and the Commons” is licensed under CC BY 4.0

We would like to acknowledge the following individuals who provided feedback and helped us shape this project: Meridith Beck Mink, Will Brucher, Conor Casey, Faithe Day, Beth Fuget, Alex Gil, Meredith Kahn, John Maclachlan, Jay Moschella, Synatra Smith, and Sarah Wipperman.

The idea of the “commons” is often invoked in discussions of the academic library’s future, but these references are usually vague and rhetorical. What exactly does it mean for the library to be organized as a commons, and what might such a library look like? Does the concept of the commons offer a useful lens for identifying the library’s injustices or shortcomings? How might we draw on the concept of the commons to see beyond the horizon of the contemporary library, toward a “Third Library” that truly advances decolonial and democratic ends?

This essay engages with such questions and explores how the constituent elements of the academic library—its knowledge assets, its workers, and its physical spaces—might be reoriented toward the commons. It argues that such an orientation might facilitate the emergence of a Third Library that is able to organize resistance to contemporary capitalism’s impetus toward the privatization and enclosure of knowledge, and to help recover a democratic conception of knowledge as a public good.

The association between libraries and the commons—which denotes either “a shared space, a resource that is shared within a community, [or] a network of ideas and concepts that are non-owned” (Berry 2005a, 61)—is one with a longstanding historical lineage (Hess and Ostrom 2007, 13). The idea of the library as a commons also continues to pervade the contemporary discourse of the academic library; witness, for instance, the proliferation of spaces within academic libraries that have been labeled as “commons” of one sort or the other (Bonnand and Donahue 2010). Perhaps most importantly, the concept of the commons exerts an imaginative and rhetorical influence over how the library views its future prospects, possibilities, and challenges.

We might observe how the concept of the commons is mobilized in discussions of the library’s future by looking at strategic plan documents, which are used by library administrators to articulate a vision for their institutions. After collecting a corpus of the most recent strategic plan documents from Research I university libraries,1 we created a word cloud from the resulting corpus to identify the most commonly used words that appear across these plans. This word cloud is presented below in Figure 1.

The word commons appears 83 times across the corpus of strategic plan documents, which does not meet the threshold for inclusion in the word cloud; as a frame of reference, the word library appears 2,908 times. Nevertheless, it is striking that many of the most frequently recurring words (which do appear in the cloud) could be construed in ways that are evocative of the library as a commons. For instance, words such as knowledge, spaces, access, open, community, diversity, center, resources, environment, preservation, and global gesture toward a vision of the library in which the commons plays some role. Yet the sheer diversity of the words that evoke the commons might suggest that this vision remains inchoate. Indeed, the very elasticity and slipperiness of the concept of the commons as it relates to the library may lead to confusion and skepticism: if “knowledge” is somehow related to the commons, just as concepts such as “spaces” or “preservation” are, might the concept of the commons be too vague to helpfully orient our thinking about the library’s future?

We believe that the concept of the commons offers a powerful tool for imagining what the future library might aspire to become. Yet, all too often, the fragmented discourse of the commons with respect to the academic library prevents us from seeing beyond the horizon of the colonial, neoliberal university, and as a result, this discourse remains unable to articulate a meaningful vision of a democratically governed academic library that serves the common good (Halperin 2020).

The commons is therefore at risk of becoming a buzzword, to the extent that it has not yet inspired a sustained effort within the library community to subject the hierarchical, exclusive, commodifying, or colonizing features of the academic library (and the university in which it is embedded) to critical scrutiny. The community has not yet meaningfully engaged with the question of how a turn toward the commons might help us to reimagine the library in light of democratic ideals, and to inscribe these ideals within the structures that constitute the library as a distinctive institution. Our goal in this essay is to offer a set of reflections on this question, and to invite others to do the same, with a view toward working together to conceptualize and build a democratic and decolonizing Third Library to accompany la paperson’s Third University.

These reflections are divided into three sections. Each section focuses on one of the academic library’s three fundamental constitutive parts:

The dynamic interplay of these elements across time shapes the library as a complex and living institution. We therefore explore how each of these aspects of the library might be reimagined and reorganized as a commons, and the obstacles that stand in the way of these efforts.

While the reflections in the following three sections are relatively self-contained, we argue that the pursuit of the commons as a governing principle within these distinct domains is ultimately an interdependent project. It is clear that neoliberal “knowledge capitalism” (Burton-Jones 1999; Olssen and Peters 2005) is at odds with our society’s traditional ideal of knowledge as a collectively owned resource that ought to advance the common good. The Third Library has an essential role to play in recovering this conception of knowledge by resisting market-driven forces of commodification and enclosure. If the library is to succeed in this role, it is essential for the library’s workers to transform the library’s workplace into a commons in its own right and thereby fortify their power and capacity for collective action. The evolution of the library into a genuine workplace democracy, in turn, will also allow the library’s workers to serve as the focal point in efforts to reconfigure the library’s physical spaces as forums for civic democratic engagement that buttress a democratic conception of knowledge as a collective resource.

1 We were able to find 116 R1 library strategic plan documents to include in the corpus; there are 131 R1 universities overall, giving us fairly good coverage. The data and code required to create the word cloud above are provided at the following link: https://github.com/aranganath24/clirproject.

One of the overarching institutional goals of the academic library is to build a “knowledge archive openly accessible to all members of society” (Argyres and Liebeskind 1998, 428). The discourse of academic libraries and librarianship often refers to this archive as a knowledge commons, which serves as a rhetorical affirmation of the principle that knowledge is an outgrowth of human social cooperation, and is thus properly understood as a collectively owned resource. The ideal of a knowledge commons is undoubtedly an inspiring one, and serves as a North Star that helps to orient the academic library’s institutional values and goals. But what, in particular, is required for the ideal of the knowledge commons to be instantiated? What is the work to be done, and what obstacles might stand in the way?

Libraries and the Possibilities of the Knowledge Commons in the Digital Age

Hess and Ostrom (2007, 13) note that libraries have long played a role as social institutions responsible for mediating access to the knowledge commons, as well as preserving and stewarding this collective knowledge on behalf of the community and future generations. In the analog era, when the knowledge stored and organized within the library was inscribed in physical, place-bound materials, the library was constrained to serve patrons within a geographically delimited locale; in the context of the academic library, this locale was the campus community, and perhaps the surrounding geographic community as well.

Academic libraries in this era mediated access to the knowledge commons using an “outside-in” service model (Dempsey and Malpas 2018), under which they acquired physical materials from various external sources and organized these materials into legible collections that their patrons could access within libraries’ physical buildings. In aspiring to become a universal library (Battles 2015), each library in effect sought to become a self-contained knowledge commons, and the library’s services aimed to facilitate access to this commons for all who entered.

This “outside-in” service model remains essential to the academic library’s identity and social role, but the digital revolution has enabled libraries to supplement this traditional relationship to the knowledge commons with a novel “inside-out” service model that expands its institutional reach (Dempsey and Malpas 2018). Under the inside-out service model that has developed in the digital age, the library devotes its efforts not simply to organizing its collections so that patrons can access the knowledge commons through the resources held within the library’s physical building (as in the outside-in model), but also to disseminating its distinctive collections and the original intellectual contributions of the university community far beyond the campus gates.

In Demsey and Malpas’s (2018) words, the “inside-out” academic library’s mission is to share….[its] institution’s unique intellectual products [including] archives and special collections, or newly generated research and learning materials (e.g., e-prints, research data, courseware, digital scholarly resources etc.)…with potential users outside the institution” (74).

Efforts to build this “inside-out” library, and thereby disseminate previously place-bound knowledge resources through digital means, is a systemic trend. One prominent example of this trend is the proliferation of institutional repositories dedicated to making university-created knowledge an accessible part of the broader knowledge commons. As different libraries pursue the project of grafting the “inside-out” library onto the traditional suite of their “outside-in” services, these individual efforts have evolved into a broader collaborative effort to build a more general knowledge archive that extends the traditional project of the knowledge commons to the digital realm.

Indeed, the institutional and disciplinary repositories that are at the heart of the “inside-out” library’s infrastructure have the potential to maintain their individual distinctiveness, while simultaneously coalescing into a more general repository of knowledge that further expands and democratizes the knowledge commons by making it accessible (in principle) to users throughout society at zero marginal cost.

We are already witnessing the emergence of such a repository in real time. Concerted efforts are gathering pace to develop common standards and conventions for these repositories, with a view toward connecting these individual knowledge archives in ways that facilitate the process of discovery for end-users. In the context of a discussion of digital open-access repositories, Suber (2012) documents this process and some of its goals:

The most useful OA repositories comply with the Open Archives Initiative (OAI) Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (PMH), which makes separate repositories play well together. In the jargon, OAI compliance makes repositories interoperable, allowing the worldwide network of individual repositories to behave like a single grand virtual repository that can be searched all at once. It means that users can find a work in an OAI-compliant repository without knowing which repositories exist, where they are located, or what they contain (55).

While this “single grand virtual repository” remains a work in progress, its emergence as a prospective goal signifies a meaningful expansion in the scope of the library’s longstanding project of helping to build, steward, and facilitate access to the knowledge commons. Moreover, the goal of building the inside-out library, and ultimately linking these libraries into a “single grand virtual repository” that might serve as a unified knowledge commons for the digital age, has also contributed to the development of novel changes in some of the library’s practices and instruments, as various innovations—spanning areas such as software, catalog search algorithms, digital repositories, digital catalogs of metadata, databases, digital curation and data management workflows—are adopted in the course of building this expanded commons. In short, these novel technologies and practices are deployed with a view toward advancing the library’s traditional goal of supporting a democratic knowledge commons, but on a more ambitious and comprehensive scale; the modern project of the knowledge commons reflects this dialectic of continuity and change.

Knowledge Capitalism Against the Knowledge Commons

This dialectic is unfolding against the backdrop of substantial changes in the political economy of capitalism. To understand the Third Library’s prospects as a steward of the knowledge commons, therefore, it is necessary to understand its relationship to this political economy.

Social scientists and observers have noted a marked shift in the past few decades, particularly in advanced industrialized countries such as the United States, “from an economy based on natural resources and physical inputs to one based on intellectual assets” (Powell and Snellman 2004, 215). These changes have shaped the emergence of a novel mode of capitalist production and accumulation, labeled “knowledge capitalism” (Burton-Jones 1999; Olssen and Peters 2005), under which the private ownership of ideas and knowledge has displaced the private ownership of tangible assets as the main wellspring of economic value creation.

Capital accumulation under this regime is driven, in other words, by private firms’ production, ownership, and deployment of ideas, rather than material things (Haskell and Westlake 2018). It is important to note that ideas are not in and of themselves naturally scarce and are therefore very different from the material substances that previously underpinned the accumulation of capital. In the parlance of economics, ideas are non-rivalrous and non-excludable, while material goods tend to be rivalrous and excludable.

Unlike material goods, therefore, ideas are not subject to natural laws of scarcity, and hence do not possess any economic value, properly understood. Before knowledge can acquire economic value and enter the circuits of capital accumulation, a complex political and legal machinery must be deployed to create robust private property rights in knowledge and artificially induce scarcity in the realm of ideas. In effect, this institutional machinery helps to transform knowledge—a naturally abundant (and hence economically valueless) resource—into a scarce and excludable (and hence economically valuable) asset that can serve as the basis for capital accumulation within the regime of knowledge capitalism (Jessop 2007).

In short, knowledge capitalism is an economic regime in which ideas and knowledge fuel capital accumulation. However, “information is not inherently valuable [and] a profound social reorganization is required to turn it into something valuable” that can be accumulated as capital (Schiller 1988, 32; quoted in Jessop 2007, 120). A central example of the institutional and legal architecture that facilitates this social reorganization is contemporary intellectual property law. Traditionally seen as a means to the end of enriching the intellectual and cultural commons, the era of knowledge capitalism has been marked by a dramatic reorientation of intellectual property law in a direction that is more solicitous of private property rights, at the expense of the commons (Brown-Keyder 2007; Vaidhyanathan 2017; Irzik 2007). Some scholars have gone so far as to argue that these changes to the intellectual property regime in the service of knowledge capitalism constitute a “second enclosure movement,” wherein the object of enclosure is not land (as in the first enclosure movement, which involved the expropriation of society’s physical commons), but knowledge itself, which entails the expropriation of the “intangible commons of the mind” (Boyle 2003, 37).

The Knowledge Commons, the Third Library, and the Politics of Resistance

Using the language of enclosure to describe the privatization and commodification of knowledge within modern processes of capital accumulation underscores the intrinsic tension between knowledge capitalism and the ideal of the knowledge commons. In particular, while the project of the knowledge commons is keyed to building and sustaining a shared repository of collectively owned knowledge for the sake of the common good, the impetus of knowledge capitalism is toward the conversion of knowledge into an excludable economic asset for the sake of private profit, which necessarily involves the enclosure of the commons.

The central challenge that libraries must confront in constructing a knowledge commons for the digital era is therefore not a technical or operational challenge, but a fundamentally political one. The challenge, in short, is to resist the encroachments of knowledge capitalism on the knowledge commons, and to defend the democratic ideal of collective access to the products of the human mind. On this account, the emergence of the Third Library as a steward of the knowledge commons will require library staff to politically mobilize in opposition to the excesses of knowledge capitalism, and in favor of a social democratic political vision that supports a decommodified view of social life that keeps faith with the ideal of knowledge as a commons.

To be sure, libraries and library staff are already involved in important political advocacy and institution-building efforts to expand the knowledge commons and defend it from enclosure. One prominent example is of course the open access movement, which aims to provide free and equitable digital access to scholarly materials that currently live behind proprietary gates established by for-profit publishers, who seek to appropriate monopolistic rents through their ownership of the journals that serve as central platforms of scholarly communication (Edlin and Rubinfeld 2004). This movement has been shaped by grassroots efforts, as well as by directives from funding agencies within the government and private sectors (McKiernan 2017).

Within universities in particular, the locus of this organizing activity has been within libraries, which bear the costs of the increasing price of journal subscriptions (i.e., the “serials crisis”) most directly (Shu et al. 2018), and whose institutional mission of expanding society’s knowledge commons is most directly constrained by barriers to open access that are erected by traditional journal publishers. Suber and Whitehead (2020) provide an account of such activities at Harvard, while the open-access efforts of library staff and stakeholders at the University of California have also received considerable attention for their role in framing a broader political agenda (Fox and Brainard 2019).

Other, related movements have also taken shape; library workers have played important agenda-setting and leadership roles in movements for open data, open science, and open source software, all of which require not only technical work, but a political vision for the future of the knowledge commons. This vision has inspired novel institutions, such as Creative Commons, which have recently been built to facilitate the sharing and distribution of intellectual and creative work on a wide scale.

However, while these efforts are to be commended, they do not explicitly offer a critique of knowledge capital or attempt to challenge its prerogatives. The open access movement offers a critique of the abusive practices of a handful of monopolistic corporations, and attempts to mobilize against them. It does not, however, explicitly question the legitimacy of the broader framework of political economy that encourages the privatization and commodification of essential public infrastructure. For example, prominent members of the open access movement take pains to emphasize that open access is entirely compatible with the very intellectual property regime that underpins knowledge capitalism (Suber 2012, 21). Though it may be true that open access can accommodate the basic institutions of knowledge capitalism, this accommodative rhetorical stance is not uncommon within contemporary movements to secure and build a democratic knowledge commons. It is a stance that attempts to finesse the inherent tensions between the broader logic of the commons and the logic of capital accumulation, rather than overcome these tensions by mobilizing politically to defend the knowledge commons against capitalist encroachment.

Another example of this politics of accommodation is Creative Commons. As Hall (2016) observes, “contrary to the way Creative Commons is frequently portrayed . . . it is not advocating a common stock of nonprivately owned (creative) works that everyone jointly manages, shares, and is free to access and use on the same basis . . . which is how the Commons is often understood”; rather, with an orientation that is fundamentally “liberal and individualistic,” it puts forward “not so much a fundamental critique of intellectual property (IP) law or a challenge to it as merely a reform of it” (Hall 2016, 4). To be sure, Creative Commons represents a step forward and deserves praise as an institutional innovation that has advanced the project of the knowledge commons; however, to the extent that it accommodates itself to the legal and institutional architecture that underpins knowledge capital, its potential role in helping to fulfill the democratic and collective possibilities of the commons is necessarily limited (Berry 2005b).

This politics of accommodation is problematic because it takes capitalist constraints on the project of the knowledge commons as given and attempts to work within those parameters, rather than reimagining the political economy and working toward a social democratic system in which those constraints are dissolved through collective action. A Third Library that accepts the subordination of the knowledge commons to knowledge capital would not be worth building, for it would represent a concession to the very forces—of commodification, enclosure, and colonization—that it is meant to challenge and overcome.

If library workers accept the need to engage in this politics of resistance for the sake of achieving a democratic knowledge commons within the Third Library, it naturally invites the question: where to begin? A logical place might be with the universities in which our libraries are embedded. These universities are increasingly important economic institutions within the regime of knowledge capitalism. Indeed, in light of the increased importance of financial autonomy in an era of public disinvestment in higher education, as well as legislative changes that have sought to foster university collaborations with private firms, universities have embraced an increasingly commercial ethos that has turned them into nodes of knowledge-based capital accumulation in their own right.

Washburn (2005), a critic of universities’ increasing orientation to the marketplace, describes various ways in which this manifests in practice:

Universities now routinely operate complex patenting and licensing operations to market their faculty’s inventions (extracting royalty income and other profits and fees in return). They invest their endowment money in risky start-up firms founded by their professors. They run their own industrial parks, venture-capital funds, and for-profit companies, and they publish newsletters encouraging faculty members to commercialize their research by going into business. Often, when a professor becomes the CEO of a new start-up, there is considerable overlap between the research taking place on campus and at the firm, a situation ripe for confusion and conflicts of interest. The question of who owns academic research has grown increasingly contentious, as the openness and sharing that once characterized university life has given way to a new proprietary culture more akin to the business world (LOC 77).

The organization of a movement to resist the increasingly prevalent commercial and proprietary culture of modern universities, which is antithetical to the ideal of the knowledge commons (and inevitably hinders librarians’ efforts to democratize access to knowledge), may therefore offer a natural starting point for a broader political effort by library workers to resist knowledge capitalism and its more general impetus toward the commodification and enclosure of knowledge and information.

This mobilization against the commodification of academic knowledge and the corporatization of the modern university, with a view toward creating the conditions necessary for the knowledge commons to flourish, would undoubtedly be contentious. Indeed, it is fraught with a greater degree of professional risk than narrower campaigns, such as the one for open access, in which library staff and other university stakeholders are able to form a unified front in fighting against the abuses of an external antagonist (i.e., for-profit journal publishers). The push to decommodify the university and reclaim the knowledge it creates as a public good is likely to engender internal opposition, particularly from university stakeholders with a vested interest in the status quo.

If library workers are to engage in the political work of building a Third Library that is a genuine steward of the knowledge commons, and in doing so successfully challenge the excesses of the corporate university that buttresses the regime of knowledge capital at the expense of the commons, it is therefore necessary to build solidarity and mutual trust among the library’s workers, so as to create the conditions necessary for mutual empowerment and collective action. It is also necessary to cultivate a civic imagination that will allow library staff, the library’s patrons, and other university stakeholders to see beyond the horizon of contemporary knowledge capitalism, and to explore ways of remaking the world through democratic, rather than market-driven, governance. Below, we explore how transposing the concept of the commons to the library workplace, and to its physical spaces, may offer us a way to meaningfully pursue these ends.

In libraries and archives, when things run smoothly and *appear* simple, you can be sure that its because of countless hours/days/weeks/years of labor behind the scenes.

— Jay Moschella (@Jay_Moschella) September 28, 2021

Library workers themselves are generally missing from discussions about the future of the library. When workers are mentioned, it is often in the context of how new types of jobs need to be created, or how existing staff need to change. The Third Library, however, places workers at its center. This Third Library might be considered what sociologists Marek Korcynski and Andreas Wittel call a “workplace commons” (2020). The workplace commons “is participatory and non-hierarchical, and it includes a specific form of collaboration, which is a collaboration beyond collegiality. It is also rooted in a sociality that is based on care for each other. It is based on explicit values such as solidarity and a belief in commoning as a superior form of organization” (722).

As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, we have seen longstanding divisions between library staff deepen. The murder of George Floyd and resulting international protests in support of Black Lives Matter in the summer of 2020 has also caused a permanent shift. Libraries have been forced to confront the whiteness of librarianship and the many failed efforts to diversify the profession.

Research from Kaetrena Kendrick and others has shown that differences in status and treatment among library staff has had an increasingly negative impact on staff morale and workplace climate (Kennedy and Garewal 2020; Kendrick and Damasco 2019; Kendrick 2017). A recent survey conducted by SPARC on the impact of the pandemic on academic libraries also found morale issues to be prevalent, and at least one respondent noted that it was causing younger library staff to leave the field entirely (Maron et al. 2021). On social media platforms like Twitter, a new genre of writing that might be called “library quit lit” has emerged, with library staff publicly posting their frustrations with their workplaces and reasons for changing careers.

I have resigned from my university job without a new job because I don't feel safe getting to or being at work during an ongoing pandemic for no reason.

— Sarah Wipperman (@swipp_it) September 23, 2021

I have also decided to leave libraries.

A thread where I bare my soul to The Internet. /1

It does not have to be that way. A Third Library that puts workers first, strives for meaningful diversity and inclusion, celebrates the many varied contributions of its staff, and appreciates all paths that lead to library work, is possible. Considering the library as a site of commoning for library workers offers one path toward a more equitable workplace for all.

The Politics of Librarianship

In 1917, the first union for library workers, the Library Employees Union, was established. Based in New York City, the union fought for equal pay and promotion opportunities for women library workers at the New York Public Library. While women made up the vast majority of librarians and library assistants, management was dominated by men. The group argued that unionization was the key toward achieving equality, and that librarians should identify as workers who were part of the production chain. Other librarians disagreed. They saw professionalization as the only way to enhance librarians’ status and increase their salaries.

The Library Employees Union believed that additional educational requirements for librarians would push out library assistants with no formal training and would result in a kind of gatekeeping that would prevent those who were not white or middle-class from entering librarianship. Dissolved in 1929, the Library Employees Union never gained much support among New York City librarians, and it never achieved its main goals (Shanley 1995). In the end, professionalism won out. However, many of the Library Employees Union’s predictions came to pass. And even today, over one hundred years later, debates about who counts as a librarian and the role of credentialing in library work show no signs of abating.

Work in academic libraries is more varied than many in the public might assume. A recent Ithaka S+R report listed 22 different job categories—including work that often receives little to no attention in library literature: facilities and security (Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg 2021). Despite the diverse range of work happening in academic libraries, staff are usually divided into two categories: professionals and paraprofessionals.

Paraprofessionals occupy a liminal place within libraries. They are not recognized or paid as librarians despite often doing similar work (Zu 2012). They may have decades of experience, or even advanced degrees, but because they often do not have a master’s degree in library science (MLS), they do not have the same advancement opportunities as librarians (Oberg et al. 1992). Consequently, the relationship between librarians and paraprofessionals is complicated. Some librarians even worry that the elevation of paraprofessionals through certifications and other means will further erode their own status as professionals (Litwin 2009; Jones and Stivers 2004). In many academic libraries that are unionized, paraprofessional staff are in different unions from librarians (who are often affiliated with faculty unions), thus further increasing the divisions between the two groups.

While increasing pathways for the advancement of paraprofessionals without the MLS has caused librarians to worry about the deprofessionalization of librarianship, the entry into the library of other professionals without the MLS, often referred to as “specialists,” has caused another kind of divide. These specialists generally have PhDs or other advanced degrees. Although debates about PhDs in the library are longstanding, the development of the CLIR Postdoctoral Fellowship Program in 2003, which places recent PhDs in academic libraries, caused an unprecedented outcry from many librarians. Despite the precarious nature of these postdoctoral positions, which generally last one to two years, critics of the program questioned whether it allowed PhDs a “fast-track entrance to coveted positions in academic libraries” (Bell 2006). These critics claimed that the program would result in a rush of PhDs entering librarianship and taking jobs from those with “only” an MLS. Subsequent research has shown that this did not actually happen (Brunner 2010).

The question about the relevance of the MLS is also tied up with recent developments in staffing in academic libraries. Libraries have been hiring functional specialists in areas such as digital scholarship, research data, scholarly communication, and publishing. These functional specialists are less likely to have an MLS (Jaguszewski and Williams 2013). In some cases, subject specialist librarians are being told that they need to become more like functional specialists. This tension causes some workers to worry that their job might be taken away, which serves to create further divisions among staff in the library (Hoodless and Pinfield 2018).

The many attempts to define who is a librarian, and who is not, have also had a negative impact on the diversity of the profession. As many scholars have noted, librarianship is defined by its whiteness (Galvan 2015). A recent Ithaka S+R survey of Association of Research Libraries members found that 71% of staff were white and 82% of librarians were white. Support staff were more likely to be people of color. Whether the library was located in a rural or urban area did not have an effect on the percentage of non-white staff members, despite library directors’ insistence that geographic location hindered their ability to attract diverse applicants (Schonfeld and Sweeney 2017). One of the implications of this is that academic librarians of color experience routine racial microaggressions from colleagues and are often treated differently than white librarians (Alabi 2015). Although there have been a number of initiatives aimed at increasing the diversity of librarians, these initiatives have generally not been successful at keeping librarians of color in the profession (Hathcock 2015). After the murder of George Floyd and the resulting international protests in support of Black Lives Matter, many libraries issued statements about anti-racism. It remains to be seen, however, if such statements will lead to any meaningful actions, especially when it comes to the hiring and retention of librarians of color. Despite a growing literature on how to diversify the profession, few libraries have taken the concrete steps needed to make real change (Vinopal 2016). In addition, recent research has shown that employees of color have been disproportionately affected by COVID-related job cuts, which could mean that academic libraries are becoming even whiter (Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg 2021).

Role of Solidarity and Collective Power

Although the percentage of all workers who are unionized in the United States has been declining over the past several decades, unionization rates for workers in higher education actually increased between 2013 and 2019 (Herbert, Apkarian, and van der Naald 2020). In 2020, 25.7 percent of librarians were union members (Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO 2021). Major unions that cover library staff include the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), the American Association of University Professors, the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), and the National Education Association (de la Peña McCook 2010). Among academic librarians, being in a union correlates strongly with faculty status. According to data from the Association of College and Research Libraries , 51% of librarians have faculty status, and 37.7% have faculty status but not tenure (Petrowski 2017). For many librarians in unions, issues related to faculty status are dominant. Recent research by Chloe Mills and Ian McCollough, however, has argued that unionization and collective bargaining are better ways to achieve gains in the workplace than fighting for faculty status (Mills and McCollough 2018).

Indeed, other higher education workers have found that it is important to focus on larger social justice issues beyond the traditional scope of bargaining. For example, a recent initiative, Bargaining for the Common Good, offers one path forward for library unions looking to do cross-coalitional work. Specifically, Bargaining for the Common Good brings together unions, community groups, racial justice organizations, and student organizations to demand that employers, governments, and other institutions (such as colleges and universities), make changes that benefit workers and the wider community (Bargaining for the Common Good n.d.; Sneiderman 2019).

Recent successful efforts at unionization offer potential roadmaps for other library staff who want to improve workplace conditions. In spring 2019, a grassroots committee of librarians, press staff, and other professional staff at the University of Washington (UW) Libraries began an organizing drive to form a union at the Libraries, eventually selecting SEIU 925, which represents the largest number of unionized staff at the university, to represent them. According to UW labor archivist Conor Casey, this move came immediately after the membership of the Associated Librarians of UW voted down pursuing faculty status after several unsuccessful attempts. Casey notes, “In this case, the failure of the effort to obtain faculty status was an enabling condition for unionization as well as an inspiration for many to try new modes of improving our working conditions” (Casey 2021). The main motivations for forming the union, according to UW staff members, were pay equity, establishing a better work-life balance, a desire for more transparency and consistency in HR policies, the desire to establish a real grievance procedure, and social justice concerns. In June 2021, the union was certified with the support of a strong majority of members. The UW Libraries Union is especially exciting because it includes librarians and other professional staff at the Libraries, the UW Press, and the UW Law Library in one bargaining unit. Currently, it consists of 180 members (Hur 2021).

First bargaining our new contract w/ UW! As the bargaining team met w/ UW reps, UWLU members welcomed new Dean Simon Neame by dropping off cookies & a welcome letter signed by 87 union members!#uwworksbecausewedo #uwlibrariesunion @SEIU925 https://t.co/eYR15KE4l2 pic.twitter.com/IWZU3L8DBq

— UW Libraries Union (@UWLibUnion) October 12, 2021

Tweet by UW Libraries Union A group of eight University of Washington Libraries Union members pose for the camera wearing SEIU shirts after their first bargaining team meeting with University of Washington representatives.

In June 2020, the University of Michigan regents approved a resolution regarding the recognition of new unions on campus. This action made it easier for new unions to form. In February 2021, librarians, archivists, and curators at the University of Michigan announced that they wanted to join the Lecturer’s Employees Organization (LEO), which is part of AFT Local 6244 and represents non-tenure track faculty across all three University of Michigan campuses (Ann Arbor, Flint, and Dearborn). Calling themselves LEO-GLAM (galleries, libraries, archives, and museums), the group represents about 176 staff members (Marowski 2021) from the University Library, the Press, the Law Library, the Business Library, and various other archives and museums on campus. Archivist Colleen Marquis explained what the group was fighting for: “Everyone deserves a workplace that is equitable, actively anti-racist, transparent, and with fair wages and a fair promotion system. Together we are now in the position to demand it. There is strength in the union” (LEO Communications Committee 2021a). In July 2021, LEO-GLAM was formally recognized by the University of Michigan (LEO Communications Committee 2021b).

Most recently, library workers at Northwestern University Libraries announced that they hope to form a union and join SEIU Local 73. If successful, the union would represent “over 130 workers who keep the library running on a daily basis, from staff who work in operations and at service points to librarians who aid faculty and students with their research” (Northwestern University Library Workers Union 2021).

We, the library workers of Northwestern University, are forming a union! Website and social media coming this afternoon. Library workers and library patrons of the world, unite! pic.twitter.com/DJKrVFC27E

— Josh (@_jshhnn) October 12, 2021

Tweet by Josh Honn A group of Northwestern University Library workers gather in front of the Rebecca Crown Center at Northwestern, where the Provost’s Office is located, to announce their intention to form a union with SEIU.

Unions have become especially important during the pandemic, as many staff have been forced to decide what is more important to them: their health or their job. Additionally, the pandemic has also resulted in a number of library workers losing their jobs. According to a recent survey from Ithaka S+R, 85% of libraries implemented some kind of staffing change because of the pandemic, including salary freezing, hiring freezes, and the elimination of open lines. They found that personnel cuts were more likely in access services; technical services, metadata, and cataloging; and facilities/operations and security (Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg 2020). Overall, the Department of Labor found that colleges and universities cut 650,000 jobs between February 2020 to February 2021, a truly remarkable number (Kroger 2021).

Of course, many public sector college and university library staff work in states that make starting or joining unions difficult if not impossible. However, as Emily Drabinski explained in a recent keynote address, even if forming a union is not possible, library staff can still build collective power within their organizations in order to bring about change (Drabinski and McElroy 2021). One example of such an effort is the United Campus Workers of Virginia, which includes custodians, librarians, staff, graduate and undergraduate workers, faculty, and advocates for better working conditions at the University of Virginia and Virginia Commonwealth University.

In addition, whether unionized or not, library staff can and should show solidarity with workers in allied fields. For example, university presses, many of which report to libraries, have also seen increased activity in unionization efforts. Oxford University Press workers recently unionized. Duke University Press staff have formed the Duke University Press Workers Union, and the group just filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board (Jaschik 2021; Publishers Weekly 2021). As Danya Leebaw and Alexis Logsdon have noted, librarians need to look for support beyond other tenured and tenure-track faculty: “Organizing and agitating alongside other third space colleagues—academic technologists, staff researchers, lecturers—might be a more effective way to capture the attention and support of protected faculty and senior administrators” (Leebaw and Logsdon 2020).

Library staff have an important role to play when it comes to building the library of the future. A Third Library is possible, but only if library workers realize that reinforcing existing statuses and hierarchies will not create positive change. Likewise, centering narrow professional concerns will also not create positive change. To create a democratic and decolonizing Third Library, library staff need to work together to create a workplace commons that draws on collective power and focuses on addressing social justice issues that affect not only library workers, but also the broader communities in which our institutions are located.

The democratic potential of the commons can be realized through a Third Library in which librarians agitate for social justice in and beyond the workplace. As we have shown, social justice in a library setting begins with the workplace commons, in which library workers have the academic and professional freedom to insist on an equitable work environment. In such an environment, it will be possible to advocate for a true knowledge commons, which inevitably will require challenging knowledge capitalism and the resulting commodification of academic knowledge in universities. The Third Library must therefore be viewed as a physical commons that provides a forum for civic engagement.

Within the physical commons of the Third Library, we imagine a place where library workers are acting in solidarity with each other, library patrons, and the larger community to create universally accessible spaces that invite collective efforts to build—and in many cases, liberate—a shared repository of collective knowledge. In this context, librarians can “reclaim their civic mission by helping constituents learn about complex public issues and practice deliberative democracy, by providing safe spaces, or commons, where students can discuss issues in a non-confrontational, non-partisan, deliberative manner” (Kranich 2010, 2-3). To position itself in this civic role, the Third Library must think creatively about commons spaces without marginalizing library workers and library services in the process, as they are essential to that civic mission.

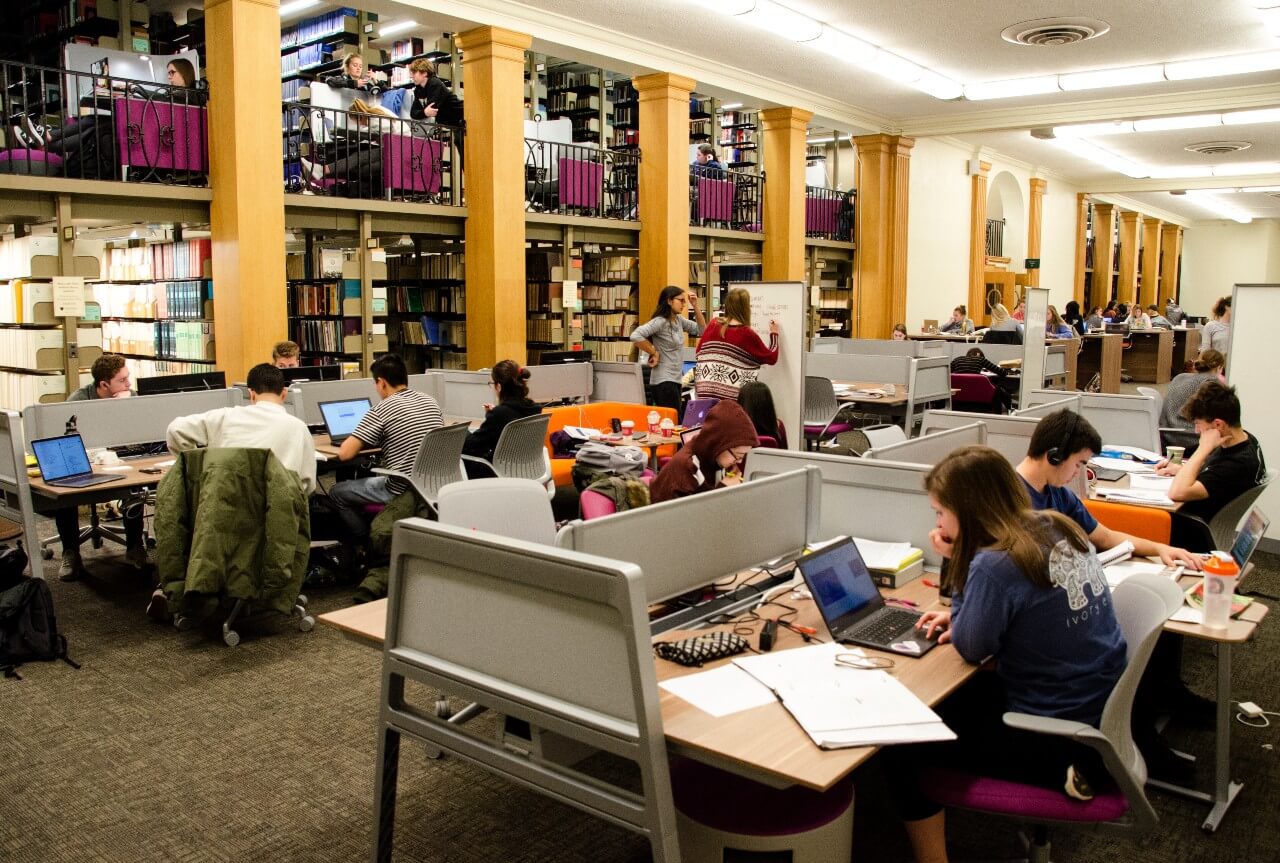

Students use library common spaces for study and collaboration. “Exam Week at ZSR” by Z. Smith Reynolds Library, Wake Forest University, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

For an example of the potential of the commons as a democratic, civic forum, we can look at the plans for the Obama Presidential Center (OPC) campus in Chicago, Illinois, originally envisioned as the Obama Presidential Center and Library. The design of the spaces and services to be offered on the OPC campus crystalize the points we have made thus far about the democratic and decommodifying possibilities of the commons in the Third Library. For instance, the Obama Presidential Center website promises that the Forum building “will serve as a place to welcome the local community—a commons designed to bring people together.” It will include an “auditorium, a broadcast and recording studio, flexible learning and meeting spaces, and a restaurant” to the community free of charge. And, through its commons, the OPC hopes to “connect the economy of the South Side of Chicago with the rest of the city, creating new jobs and opportunities” (Obama Foundation 2021a). At the OPC groundbreaking ceremony in September 2021, Barack Obama promised that the Center “won’t just be an exercise in nostalgia or looking backwards. We want to look forward” (Vigdor 2021).

Today, we officially broke ground on the Obama Presidential Center on the South Side of Chicago. Michelle and I can’t imagine a better investment in the city we love, and generations of young leaders who will help create change. pic.twitter.com/cmyD0pD4jy

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) September 28, 2021

Tweet by Barack Obama with images of Obama Presidential Center groundbreaking ceremony.

Indicative of movements such as “the intellectual commons, library-as-space, and technology-aided learning,” which aim to make “the library a place offering access to information and knowledge in all of its formats as well as the space and technology to access and use that information” (Bonnand and Donahue 2010, 227), the OPC articulates a vision for a commons that provides resources and spaces shared equally among community members.

Like academic libraries, the OPC faces both opportunities and challenges brought about by the growing number of born-digital records and rapid changes in information technologies. The OPC will be the first fully digital presidential library, which makes sense, as about 95% of the records from the Obama presidency were born digital (Obama Foundation 2019). The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) “will have a staff dedicated to preserving, reviewing, and providing access to the Presidential Records of the Obama Administration. They will help the public, including historians and other researchers, find and access the born-digital and digitized records (ibid). As a result, the center is poised to maximize access to its physical spaces—a priority of most academic libraries. In fall 2019, nearly all respondents to an Ithaka S+R Library Survey reported that providing physical spaces for independent and collaborative student learning was a priority (Frederick and Wolff-Eisenberg 2020).

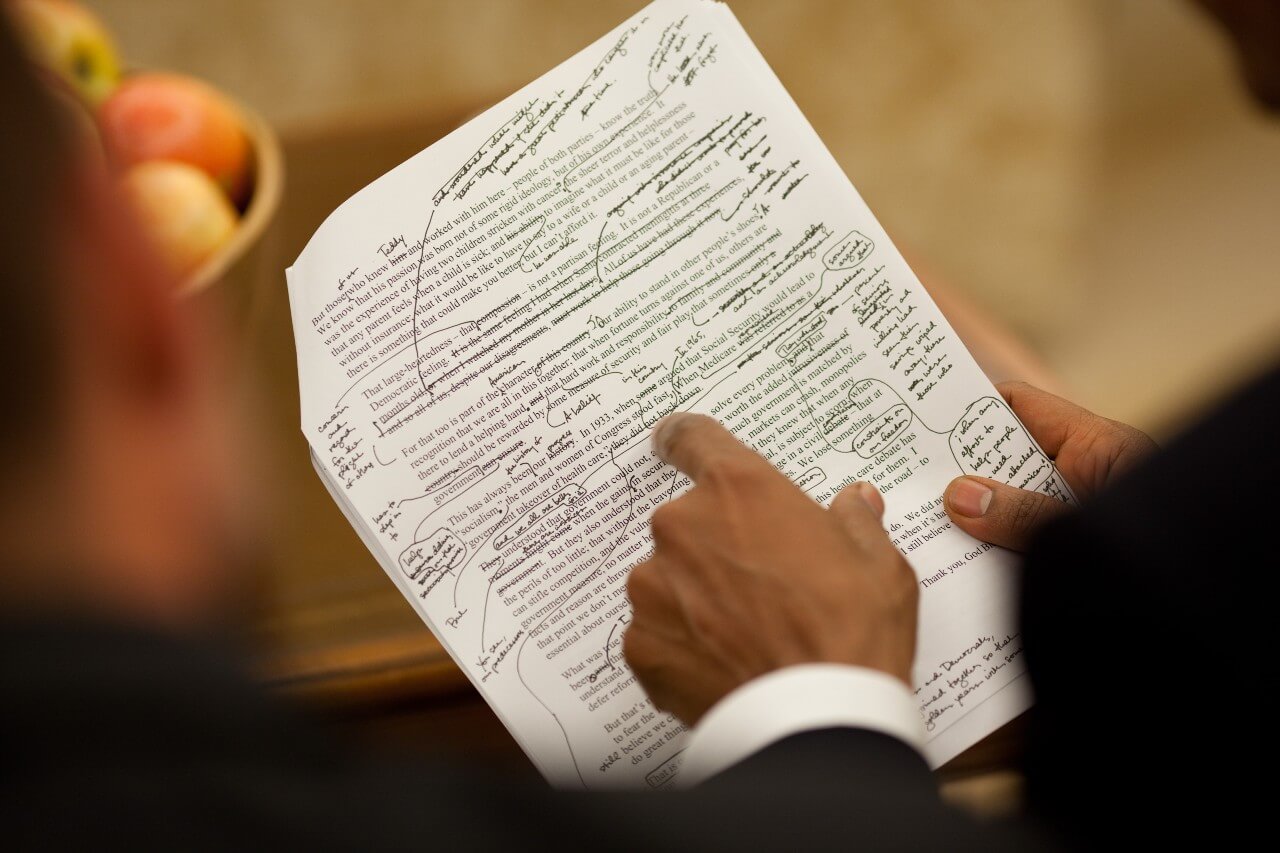

NARA will digitize all records from the Obama presidency that were not born digital for inclusion in the fully digital Obama Presidential Library. “President Barack Obama and Jon Favreau, head speechwriter, edit a speech on health care in the Oval Office, Sept. 9, 2009, in preparation for the president’s address to a joint session of Congress.”Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

This first fully digital presidential library constitutes more than one break in precedent, as the staff and the collections they oversee will not be located onsite. There will be no research library located on the OPC campus, and the librarians, archivists, technologists, and other information professionals responsible for the collection will be located at NARA headquarters in Washington, DC. Moving the research library and its staff offsite overlooks the affordances of having librarians and preservation staff centrally located in the commons and therefore provides a warning to academic libraries to avoid devaluing or altogether eliminating library staff and library services in the physical commons. In this case, “NARA’s archival staff are dedicated, highly skilled professionals. But it’s impossible for an archivist in Washington, DC, or at another large records-storage facility to have deep subject matter knowledge of the billions of records at that location” (Clark 2018, 102).

This deep subject matter expertise will not be available to the community that the space is being designed to serve and it will likely be lost due to thinking of the presidential library as simply a large records-storage facility. Furthermore, the digitization of and digital access to the historical record are being treated as affordances that allow the OPC to focus exclusively on access to physical spaces. While creating inclusive, welcoming spaces is a noteworthy pursuit, it cannot be done at the expense of a dedicated library staff. Instead of viewing digital infrastructure as behind the scenes and therefore easily outsourced or decentralized, the library of the future has the opportunity to make visible the importance of librarians’ labor by integrating the technological infrastructure into its building operations.

We should acknowledge the library, as Shannon Mattern suggests, as an intersecting system of “infrastructural ecologies—as sites where spatial, technological, and social infrastructures shape and inform one another” (2014). Mattern points to the New York Public Library Labs and Harvard’s Library Test Kitchen as examples of “what’s possible when even back-of-house library spaces become sites of technological praxis. Unfortunately, those innovative projects are hidden behind the interface (as with so much library labor). Why not bring those operations to the front of the building, as part of the public program?” (Mattern 2014). Making librarians’ labor a visible centerpiece of the activities of the commons will counteract the invisibility of librarianship that often leads to a devaluing of library services. Moreover, teaching students to recognize the impact of technology on knowledge production and circulation will involve them in the project of remaking the knowledge commons by resisting market-driven governance. This “[r]ethinking the library from an anti-capitalist commons perspective means upholding the value of the library worker, of the daily interactions that make the instruction, the arranging, and the describing useful and significant” (Halperin 2020).

To return to the example of the OPC, moving library staff offsite to manage the presidential papers constitutes a missed opportunity that academic libraries should take note of when envisioning a Third Library. The born-digital records that comprise 95% of the presidential records should not be an excuse for moving the records off-site for preservation by NARA professionals, but rather an occasion to engage the community in the implications of the new media landscape for Obama’s presidency and its legacy. For instance, a legacy media lab staffed by librarians and technologists could allow patrons to explore the emerging technologies, social media platforms, and multimedia content central to the campaigning and activism at the heart of the Obama presidency. This would further the goals articulated by President Obama “not to just create a monument to my presidency, but rather to describe for anyone who visits, how Michelle and I and so many others stood on the shoulders of those who had fought the good fight before us. And hopefully that then will inspire a new generation of activists” (Obama Foundation 2021b). A commons that encourages exploration of this legacy, particularly the ways people have harnessed technology to create new ways of engaging in the democratic process, should be a central feature of the Third Library.

The Recover Analog and Digital Data lab (RADD) at the University of Wisconsin’s Information School Library. Photograph by Carrie Johnston is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The library worker’s role is indispensable in cultivating a commons that explores and facilitates a knowledge of the ways technology informs how we consume, create, and exchange information. To create a Third Library, we must rethink the familiar patterns of outsourcing library work and making librarians’ labor invisible. For too long library work has been hidden behind the scenes, particularly in the digital age in which linked data and information architecture are often taken for granted. As Mattern asks, “With the increasing recession of these technical infrastructures—and the human labor that supports them—further off-site, behind the interface, deeper inside the black box, how can we understand the ways in which those structures structure our intellect and sociality?” (2014).

One potential solution is to design physical commons in libraries that encourage students to create digital content. For example, Kate Winger-Playdon, associate dean and director of architecture and environmental design at the Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University, acknowledges that the “concept of research has changed and the [Charles] library reflects that in a really interesting way. Whereas one thinks about research as scholarly research, using books, we can now think about research as having a creative side. And the library reflects this by having spaces for making things: makerspaces, digital tools, places for collaboration” (Temple University 2019). In creating a commons that encourages creative scholarship, academic libraries are also encouraging students to think critically about both the opportunities of creating born-digital content that can contribute to a democratic knowledge commons and the challenges of circulating this digital content in systems that are built to sustain knowledge capitalism.

The Charles Library at Temple University. “Temple_Univ (13) by Michael Stokes is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

We have highlighted the OPC campus as an example of a remarkable commons space that will include resources similar to those found in academic libraries—digital labs, learning and meeting rooms, and recording studios—but nonetheless whose democratic potential we believe has been compromised by the absence of librarians in the physical commons. It seems that by moving the responsibilities of shelving, indexing, cataloging, digitizing, and providing research space offsite, the OPC can better focus on the community it serves. As we have shown, however, librarians play a crucial role in “naming, framing, convening and moderating deliberative forums that teach students how to make public choices together and demonstrate the value of the deliberative process as a curricular tool” (Kranich 2019).

With the OPC and library conceived as separate endeavors, the commons spaces on the OPC campus in Chicago risks depriving the community of the deliberative forums that librarians have the experience and skills to cultivate. The first fully digital presidential library would benefit from librarians who can involve the public in this unprecedented change in how we interact with and learn from a former president’s papers. As Dan Cohen argues, “In the same way that the Obama Presidential Center has invested in designing a building for its events, activities, and community, now is the time for it to design an information architecture for a digital presidential library, thinking about the structures that will enable—or hinder—the discovery and analysis of Obama’s record and the record of our country during his presidency” (Cohen 2019). As we have shown, there is even greater potential for democratic and civic discourse if library staff are located onsite and can provide instruction in critical information literacy that will help create a knowledge commons through engaging with the digital presidential library.

Academic libraries should take note of this tendency, seen in the design of the Obama Presidential Center, to devalue or eliminate librarians’ work from the commons due to online services. As Marie L. Radford points out, such services “seem deceptively simple because we live online now, but what’s underneath there is the level of complexity about human interaction” (qtd. in Carlson 2021). Additionally, academic libraries must take note that when building knowledge commons, we must avoid the paradox in which faculty “vote to protect the collections budgets from cuts while allowing, directly or indirectly, reductions in staff that prevent the very acquisitions and systems design and other services needed to bring them the collections they defended” (Pritchard 2008, 299). Library work must be a centerpiece not only in building the knowledge commons, but also advocating for free and open access to information and resisting the encroaching demands of knowledge capitalism. A Third Library is possible when building physical spaces that allow for the collective power of a workplace commons, which in turn makes it possible to advocate for a true knowledge commons.

The commons might be conceptualized, in broad terms, as “those assemblages and ensembles of resources that human beings hold in common or in trust to use on behalf of themselves, other living human beings, and past and future generations of human beings, and which are essential to their biological, cultural, and social reproduction” (Nonini 2006, 164).

Despite the pervasiveness of library rhetoric that appeals to the “commons,” academic libraries are complicit in the capitalist and colonial projects of commodifying and enclosing the commons. As la paperson has noted, “land accumulation as institutional capital is likely the defining trait of a competitive, modern-day research university” (2017, 25). To the extent that academic libraries are part of a university system that is built on expropriated and commodified land, they are therefore part of a broader complex of “settler colonial technologies” such as “land tenancy, debt, and the privatization of land . . . that enable the ‘eventful’ history of plunder and disappearance” (2017, 3). There is no escaping this legacy, but in confronting and coming to terms with it, we might more effectively undertake the work of remaking the capitalist and colonial university into a social democratic institution that serves the common good.

To transform the contemporary academic library into a Third Library that “hotwire[s] the university for decolonizing work” along these lines (la paperson 2017, 32), library staff must push the university, and society at large, to recover a shared appreciation for the commons and its liberating possibilities. Such an effort will require library workers and the library’s stakeholders to reflect on how the academic library, in particular, might be reconfigured for such a purpose and transformed into a genuine commons in its own right.

However, while the concept of the commons plays a prominent role in the discourse of the academic library, it is typically deployed as a rhetorical buzzword, rather than a framework for articulating a coherent and compelling vision for the library’s future that attempts to redress the shortcomings of its past. Therefore, our goal has been to contribute to a more critical dialogue on the library as a commons that others have started (Halperin 2020), with a view toward using the concept of the commons to challenge existing institutions and practices, and to imagine the path to a future library that actualizes the democratic and decolonizing possibilities that already lie within it.

In attempting to reimagine the academic library as a genuinely democratic and inclusive Third Library that advances these ends, our approach has been to identify and disaggregate the contemporary library’s essential constituent parts—its knowledge assets, its workers and their labor, and the physical spaces that underpin its social relations—and explore how we might push these distinct, yet interrelated, aspects of the library to more fully approximate the commons ideal.

Taken together, these interrelated reflections on the Third Library as a commons cohere into a broader program of transformation, one that is especially urgent in a world where universities are accelerating their enclosure of the commons by positioning themselves as strategically important sites within the circuits of knowledge capital that are oriented to the “production, circulation, and accumulation of value, materialised in the form of rents and surpluses on operating activities” (Hall 2020, 830). This orientation is at odds with the essential ideals that draw many of us to the work of librarianship, which are perhaps best summarized by Hess and Ostrom (2007), who observe that “the discovery of future knowledge is a common good and a treasure we owe to future generations,” and that “[keeping] the pathways to discovery open” is an important aspect of our collective democratic flourishing (13).

As a social institution, the Third Library has the potential to play an essential role in resisting this movement toward enclosure and helping fulfill the vision of free and equitable access to knowledge as an essential aspect of the common good. There is nothing inevitable about this library’s emergence, however. We have argued that it will require concerted efforts on the part of the library’s workers to build their collective power and to forge the bonds of solidarity that necessarily underpin successful collective action. As they work to build this collective power and solidarity, we imagine that the library’s workers will be empowered to insist on the primacy and visibility of their labor. This, in turn, will fortify their efforts to reimagine and reorganize the library’s physical spaces, with a view toward inspiring the civic engagement and democratic participation that might breathe life into a Third Library that is at once the embodiment and caretaker of a revitalized commons.

(January 2022)

Alabi, Jaena. 2015. “Racial Microaggressions in Academic Libraries: Results of a Survey of Minority and Non-minority Librarians.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 41(1): 47-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2014.10.008.

Argyres, Nicholas S. and Julia Porter Liebeskind. 1998. “Privatizing the Intellectual Commons: Universities and the Commercialization of Biotechnology.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 35(1998): 427-454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(98)00049-3.

Bargaining for the Common Good. n.d. https://www.bargainingforthecommongood.org/.

Battles, Matthew. 2015. Library: An Unquiet History. London: WW Norton and Company. Kindle Edition.

Bell, Steven. 2006. “CLIR’s Program: A Real or Imagined Shortage of Academic Librarians.” ACRLog (October 16). https://acrlog.org/2006/10/16/clirs-program-a-real-or-imagined-shortage-of-academic-librarians/.

Berry, David M. 2005a. “The Commons as an Idea-Ideas as a Commons.” Free Software Magazine 1 (February): 61-64.

Berry, David M. 2005b. “On the ‘Creative Commons’: A Critique of the Commons Without Commonality.” Free Software Magazine. http://freesoftwaremagazine.com/articles/commons_without_commonality/.

Bonnand, Sheila and Tim Donahue. 2010. “What’s in a Name? The Evolving Library Commons Concept.” College and Undergraduate Libraries 17(2-3): 225-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691316.2010.487443.

Boyle, James. 2003. “The Second Enclosure Movement of the Public Domain.” Law and Contemporary Problems 66(33): 33-74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20059171.

Brown-Keyder, Virginia. 2007. “Intellectual Property: Commodification and its Discontents.” In Reading Karl Polanyi for the 21st Century: Market Economy as a Political Project, edited by Ayse Bugara and Kaan Agartan, 155-173. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Brunner, Marta L. 2010. “PhD Holders in the Academic Library: The CLIR Postdoctoral Fellowship Program.” In The Expert Library: Staffing, Sustaining, and Advancing the Academic Library in the 21st Century, edited by Scott Walter and Karen Williams. Chicago: Association of College & Research Libraries: 158–189. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/05j228r4.

Burton-Jones, Alan. 1999. Knowledge Capitalism: Business, Work, and Learning in the New Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carlson, Scott. 2021. “Academic Libraries Led Universities Into the Socially Distant Era. Now They’re Planning for What’s Next.” The Chronicle of Higher Education (April 27). https://www.chronicle.com/article/academic-libraries-led-universities-into-the-socially-distant-era-now-theyre-planning-for-whats-next.

Casey, Conor. 2021. Correspondence with Annie Johnson.

Clark, Bob. 2018. “In Defense of Presidential Libraries: Why the Failure to Build an Obama Library is Bad for Democracy.” The Public Historian 40(2): 96-103.

Cohen, Dan. 2019. “Obama’s Presidential Library Is Already Digital.” The Atlantic (April 9). https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/04/obamas-presidential-library-should-be-digital-first/586693/.

De la Peña McCook, Kathleen. 2010. “Unions in Public and Academic Libraries.” School of Information Faculty Publications 108. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/si_facpub/108.

Dempsey, Lorcan and Constance Malpas. 2018. “Academic Library Futures in a Diversified University System.” In Higher Education in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, edited by Nancy Gleason, 65-91. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Department for Professional Employees, AFL-CIO. 2021. “Library Professionals: Facts & Figures.” https://www.dpeaflcio.org/factsheets/library-professionals-facts-and-figures#_edn15

Drabinski, Emily, and Kelly McElroy. 2021. “Building Our Power: Management and Labor in Libraries.” CALM Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uOhpj8vYgn8.

Edlin, Aaron S. and Daniel L. Rubinfeld. 2004. “Exclusive or Efficient Pricing? The Big Deal Bundling of Academic Journals.” Antitrust Law Journal 72(1): 119-157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40843619.

Fox, Alex and Jeffrey Brainard. 2019. “University of California Takes a Stand on Open Access.” Science 363(6431): 1023. DOI: 10.1126/science.363.6431.1023-a.

Frederick, Jennifer and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg. 2020. “Academic Library Strategy and Budgeting During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2020.” Ithaka S+R (December). https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.314507.

Frederick, Jennifer and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg. 2021. “National Movements for Racial Justice and Academic Library Leadership: Results from the Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2020.” Ithaka S+R (March). https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.314931.

Galvan, Angela. 2015. “Soliciting Performance, Hiding Bias: Whiteness and Librarianship.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (June 3). https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/soliciting-performance-hiding-bias-whiteness-and-librarianship/.

Hall, Gary. 2016. Pirate Philosophy: For a Digital Posthumanities. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Hall, Richard. 2020. “The Hopeless University. Intellectual Work at the End of the End of History.”

Postdigital Science and Education 2: 830-848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00158-9.

Halperin, Jennie Rose. 2020. “The Library Commons: An Imagination and an Invocation.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (September 2). https://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2020/the-library-commons/.

Haskell, Jonathan, and Stian Westlake. 2018. Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hathcock, April. 2015. “White Librarianship in Blackface: Diversity Initiatives in LIS.” In the Library With the Lead Pipe (October 7). http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2015/lis-diversity/.

Herbert, William A., Jacob Apkarian, and Joseph van der Naald. 2020. “Supplementary Directory of New Bargaining Agents and Contracts in Institutions of Higher Education, 2013-2019.” National Center for the Study of Collective Bargaining in Higher Education and the Professions, Hunter College, City University of New York. https://webedit2.hunter.cuny.edu/ncscbhep/assets/files/SupplementalDirectory-2020-FINAL.pdf.

Hess, Charlotte, and Elinor Ostrom. 2007. “Introduction: An Overview of the Knowledge Commons.” In Understanding Knowledge as a Commons, edited by Charlotte Hess and Elinor Ostrom, 3-27. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hoodless, Catherine, and Stephen Pinfield. 2018. “Subject vs. Functional: Should Subject Librarians Be Replaced by Functional Specialists in Academic Libraries?” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 50(4):345–60. http://www.doi.org/10.1177/0961000616653647.

Hur, Soohyung. 2021. “Overdue: UW Libraries Staff Organize Across Three Campuses to Form New Union.” Building Bridges: The Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies Newsletter: 31 (October).

Irzik, Gurol. 2007. “Commercialization of Science in a Neoliberal World.” In Reading Karl Polanyi for the 21st Century: Market Economy as a Political Project, edited by Ayse Bugara and Kaan Agartan, 135-155. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jaguszewski, Janice, and Karen Williams. 2013. “New Roles for New Times: Transforming Liaison Roles in Research Libraries.” Association of Research Libraries. https://hdl.handle.net/11299/169867.

Jaschik, Scott. 2021. “Duke University Press Workers Seek Union.” Inside Higher Ed (March 30). https://www.insidehighered.com/quicktakes/2021/03/30/duke-university-press-workers-seek-union.

Jessop, Bob. 2007. “Knowledge as a Fictitious Commodity: Insights and Limits from a Polanyian Perspective.” In Reading Karl Polanyi for the 21st Century: Market Economy as a Political Project, edited by Ayse Bugara and Kaan Agartan, 115-135. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jones, Philip and James Stivers. 2004. “Good Fences Make Bad Libraries: Rethinking Binary Constructions of Employment in Academic Libraries.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 4(1): 85-104. http://www.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2004.0011.

Kendrick, Katrena Davis, and Ione T. Damasco. 2019. “Low Morale in Ethnic and Racial Minority Academic Librarians: An Experiential Study.” Library Trends 68(2): 174-212. http://www.doi.org/10.1353/lib.2019.0036.

Kendrick, Kaetrena Davis. 2017. “The Low Morale Experience of Academic Librarians: A Phenomenological Study.” Journal of Library Administration 57(8): 846-878. http://www.doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2017.1368325.

Kennedy, Sean P., and Kevin R. Garewal. 2020. “Quantitative Analysis of Workplace Morale in Academic Librarians and the Impact of Direct Supervisors on Workplace Morale.” The Journal of Academic Librarianship 46(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2020.102191.

Korcynski, Marek, and Andreas Wittel. 2020. “The Workplace Commons: Toward Understanding Commoning within Work Relations.” Sociology 54(4). http://www.doi.org/10.1177/0038038520904711.

Kranich, Nancy. 2019. “Academic Libraries as Civic Agents.” In Discussing Democracy: A Primer on Dialogue and Deliberation in Higher Education, edited by Timothy J. Shaffer. https://doi.org/10.7282/t3-zn3f-6a39.

Kranich, Nancy. 2010. “Academic Libraries as Hubs For Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Public Deliberation, 6(1): 1-15. https://doi.org/10.7282/T3B85C63.

Kroger, John. 2021. “650,000 Colleagues Have Lost Their Jobs: A Moral Issue for Higher Education.” Inside Higher Ed (February 19). https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/leadership-higher-education/650000-colleagues-have-lost-their-jobs.

la paperson. 2017. A Third University is Possible. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. Kindle Edition.

Leebaw, Danya, and Alexis Logsdon. 2020. “Power and Status (and Lack Thereof) in Academe: Academic Freedom and Academic Librarians.” In the Library with the Lead Pipe (September 16). http://www.inthelibrarywiththeleadpipe.org/2020/power-and-status-and-lack-thereof-in-academe/.

LEO-GLAM Communications Committee. 2021a. “LEO-GLAM: ‘There is Strength in the Union.’” LEO Blog (June 10). https://leounion.org/blog/2021/6/10/leo-glam-there-is-strength-in-the-union.

LEO-GLAM Communications Committee. 2021b. “LEO-GLAM: Achievement Unlocked! Card Check Edition.” LEO Blog (July 18). https://leounion.org/blog/2021/7/17/leo-glam-achievement-unlocked-card-check-edition.

Litwin, Rory. 2009. “The Library Paraprofessional Movement and the Deprofessionalization of Librarianship.” The Progressive Librarian 33: 43-60. http://www.progressivelibrariansguild.org/PL/PL33/043.pdf.

Maron, Nancy, Juan Pablo Alperin, and Nick Shockey. 2021. “SPARC COVID Impact Survey: Better Understanding Libraries’ Approach to Navigating the Pandemic and & Its Impact on Support for Open Initiatives.” https://sparcopen.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/SPARC-COVID-Impact-Survey-092021.pdf.

Marowski, Steve. 2021. “Librarians, Archivists, Curators Seek to Unionize at University of Michigan.” M Live (February 26). https://www.mlive.com/news/ann-arbor/2021/02/librarians-archivists-curators-seek-to-unionize-at-university-of-michigan.html.

Mattern, Shannon. 2014. “Library as Infrastructure.” Places Journal. Available at https://placesjournal.org/article/library-as-infrastructure/.

McKiernan, Erin C. 2017. “Imagining the ‘Open’ University: Sharing Scholarship to Improve Research and Education.” PLoS Biology 15(10): 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002614.

Mills, Chloe, and Ian McCullough. 2018. “Academic Librarians and Labor Unions: Attitudes and Experiences.” portal: Libraries and the Academy 18(4): 805-829. http://www.doi.org/10.1353/pla.2018.0046.

Nonini, Donald M. 2006. “Introduction: The Global Idea of the Commons.” Social Analysis 50(3): 164-177. https://doi.org/10.3167/015597706780459368.

Northwestern Library Workers Union. 2021. https://sites.google.com/view/nulwu/home.

Obama Foundation. 2021a. The Obama Presidential Center. Available at https://www.obama.org/the-center/.

Obama Foundation. 2021b. Special Reveal: See the text that will appear on the Obama Presidential Center Museum. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XBTFbK8bMJQ.

Obama Foundation. 2019. Fact Sheet: The Obama Presidential Archives. Available at https://www.obama.org/updates/obama-presidential-archives-fact-sheet/.

Oberg, Larry R., Mark E. Mentges, P. N. McDermott, and Vitoon Harusadangkul. 1992. “The Role, Status, and Working Conditions of Paraprofessionals: A National Survey of Academic Libraries.” College & Research Libraries 53(3): 215-238. https://crl.acrl.org/index.php/crl/article/view/14714/16160.

Olssen, Mark, and Michael A Peters. 2005. “Neoliberalism, Higher Education, and the Knowledge Economy: From Free Market to Knowledge Capitalism.” Journal of Education Policy 20(3): 313-345. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500108718.

Petrowski, Mary. 2017. Academic Library Trends and Statistics. Chicago: Association of College & Research Libraries.

Powell, Walter, and Kaisa Snellman. 2004. “The Knowledge Economy.” Annual Review of Sociology 30: 199-220. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100037.

Pritchard, Sarah M. 2008. “Deconstructing the Library: Reconceptualizing Collections, Spaces and Services.” Journal of Library Administration 48(2): 219-233. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930820802231492.

Publishers Weekly. 2021. “DUP Workers Union Files for NLRB Election.” https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/newsbrief/index.html?record=3237.

Schiller, Dan. 1988. “How to Think About Information.” In The Political Economy of Information, edited by V. Mosco and J.Wasko, 27-44. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Schonfeld, Roger, and Liam Sweeney. 2017. “Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity: Members of the Association of Research Libraries: Employee Demographics and Director Perspectives.” Ithaka S+R. https://doi.org/10.18665/sr.304524.

Shanley, Catherine. 1995. “The Library Employee’s Union of Greater New York, 1917-1929.” Libraries & Culture 30(3): 235-264.

Shu, Fei, Philippe Mongeon, Stefanie Haustein, Kyle Siler, Juan Pablo Alperin, and Vincent Larivieri. 2018. “Is it Such a Big Deal? On the Cost of Journal Use in the Digital Era.” College and Research Libraries 79(6): 785-798. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl.79.6.785.