Written By

Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio, Temple University Libraries1 and College of Education, Temple University2

The Virtual Blockson is a project that utilizes virtual reality (VR) to teach high school students primary source literacy using materials from the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection (Blockson Collection) housed at the Temple University Libraries.The Blockson Collection, comprising over 700,000 items related to the African Diaspora, includes a multitude of materials types such as books, sheet music, manuscripts, photographs, sculptures, and films. This rich variety of materials, covering a broad range of topics and time periods, is suited to gamification via a multi-modal medium like VR. In addition to the VR game itself, accompanying teaching guides, onboarding materials for teachers and players, and stand alone 3D models will be created to situate the game within a broader social studies curriculum. The completion of the game, in tandem with accompanying teaching materials, will allow students to meet the learning objectives laid out in the Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy developed by a joint task force on behalf of the Association of College and Research Libraries Rare Books and Manuscripts Section (ACRL/RBMS) and the Society of American Archivists (SAA).

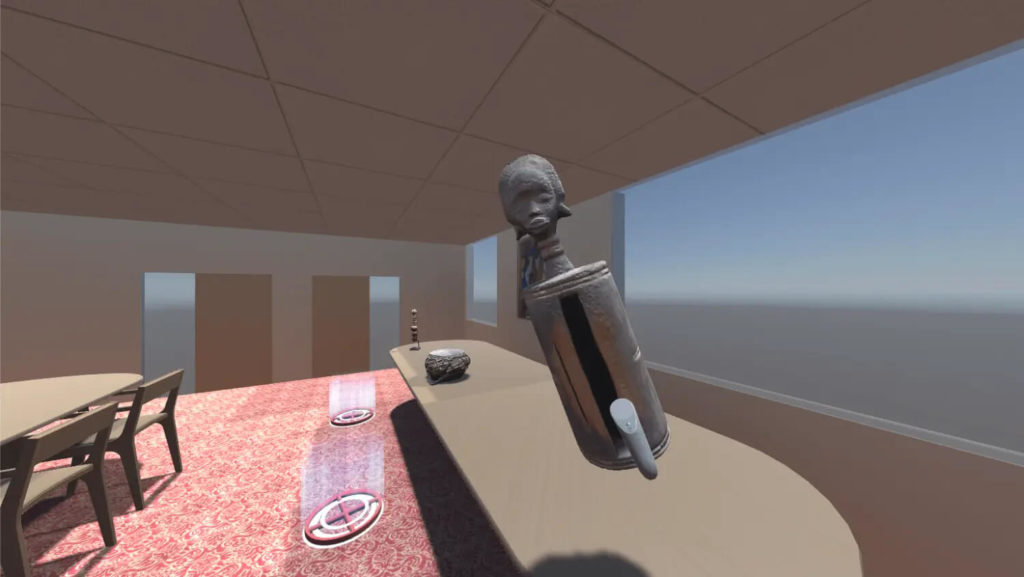

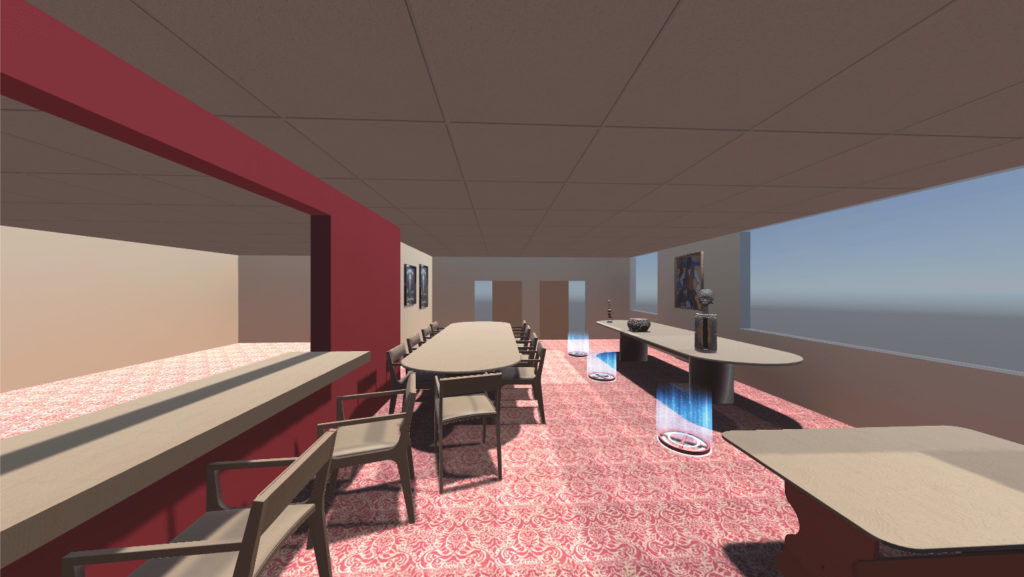

To support this work, the Temple University Libraries Loretta C. Duckworth Scholars Studio (Scholars Studio) and Blockson Collection have developed a collaborative project to support the development of a prototype that will feature a level of the game focusing on the Pyramid Club. Using photos from the Blockson Collection’s John W. Mosley collection, primary and secondary sources from the collection, as well as supplementary materials from related archives and museums, this prototype will introduce students to Black art and artists during the 1940’s. We will also produce an accompanying teaching toolkit, consisting of teaching materials and onboarding documentation for teachers. Accessibility testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More for disability, documenting accessibility approaches, general user testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More for gameplay, assessment of the pedagogical efficacy of the game, and assessment of the sufficiency of the teaching toolkit will also take place during this phase of work.

Students will be provided with a research question on one of four categories related to Black life in the United States: sports, leisure, arts and culture, and protests. For this prototype, the art and artists connected to the Pyramid Club, part of the arts and culture category, are the focus. While there will be a general introduction to twenty-four artists that appear in Mosley’s photos of the club, only Laura Wheeler Waring and Dox Thrash will have fully developed tracks in the finished prototype. These two artists were selected for the unique aspects of Black life and identity that their stories introduce. They differed from one another in gender, artistic style and medium, socio-economic status, region of origin, and commercial success. These differences show the unique challenges Black Americans faced, as well as the different ways they pursued success. We discuss Wheeler Waring and Thrash further below.

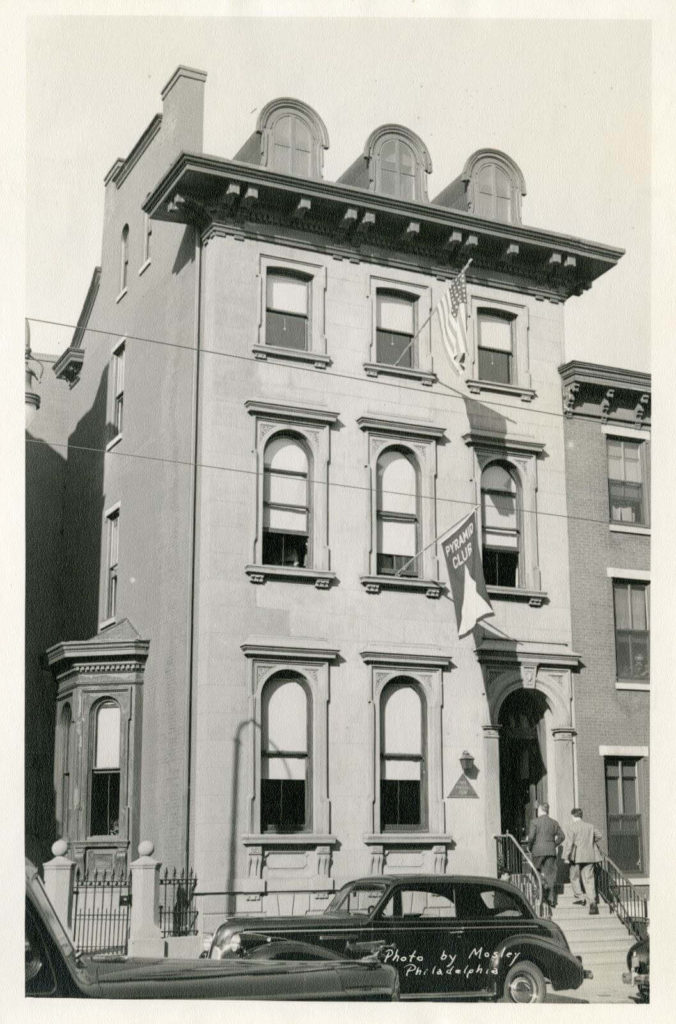

The Pyramid Club, established in 1937 for the “cultural, civic and social advancement of Negroes in Philadelphia” (Brigham, 2008), was founded by Theodore Spaulding, a Philadelphia lawyer and local chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). His goal was to create a space that “could successfully group together representative citizens of different political and religious faiths and occupations” (Brigham, 2008) within Philadelphia. Its members were Black middle- and upper-class professionals including physicians, dentists, lawyers, and businessmen and it quickly became an important space for socializing and the arts. It organized and created a meeting place for civic activities, professional meetings, fashion shows, society weddings, entertainment events, parties, lectures, and annual art exhibitions. In particular, its annual art exhibitions became major events that attracted many artists that would become prominent figures in African American art like Dox Thrash, Selma Burke, and Romare Bearden.

Many prominent figures can be seen visiting the Pyramid Club in photos taken by the African American Philadelphia-area photographer John W. Mosley. Temple University Libraries (n.d.) summarized Moseley’s trajectory and impact thusly:

A witness and chronicler of the many changes in politics, culture, sports and fashion from the late 1930s to the late 1960s [who] photographed many prominent figures in the African American community. His subjects included Marian Anderson, Martin Luther King, Jr., Paul Robeson, Cab Calloway, W.E.B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, players of the Negro Baseball League, and many others. Many of his photographs were taken in Philadelphia and Atlantic City, but he also worked in New York, Baltimore, and Washington D.C.

His photographs of the Pyramid Club capture the visits of important figures such as Kwame Nkrumah, Mary McLeod Bethune, Josephine Baker, and Samuel L. Evans, among others. While players will encounter materials beyond Mosley’s photos, his photos will act as a starting point from which our team can choose events and figures for inclusion in the game.

Laura Wheeler Waring was a prominent African American artist born in 1887 in Hartford, Connecticut to an educated, middle-class family. She is known for her portraits of prominent African Americans, an emphasis on combating derogatory depictions of Black people, a dedication to teaching, her work in The Crisis, and general service to the use of the arts to further civil rights activism. In 1906 she would head to Philadelphia to study at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts before going on to receive a scholarship to study abroad in Europe in 1914. Following her return to the United States, she would found, teach, and chair the music and art departments at the Cheyney Training School for Teachers (now Cheyney University of Pennsylvania), originally located in Philadelphia. Wheeler Waring was the most prolific female artist to contribute to The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, founded and edited by her good friend and fellow New Englander, W.E.B. Du Bois (Kirschke, 2014). In her work and correspondence one sees a constant desire to combat stereotypical depictions of Black people. This was not only apparent in her work for The Crisis, but in the portraits she painted of Black individuals who had done work to progress the rights of the African American community. Wheeler Waring’s experience as a Black woman will be key to this track. Women, especially Black women, were often excluded from receiving funding, creating certain types of art, and furthering their health and careers in general. This can be seen in Du Bois’s rejection of certain women on the basis that he did not feel that they were ready to represent the race (Kirschke, 2014, pp. 89). This intra-community gate-keeping would impact all African American female artists in different ways, but it is doubtless that Wheeler Waring’s more conservative approach to her work and social justice, which emphasized building allies via respectability, contributed to her success. This is not to say that she did not have to fight. She was underpaid and often paid late for her work in The Crisis (Kirschke, 2014, pp. 113; Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2021). Also, her conservative approach was not without critique by those same, male gate-keepers (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2021). By having students engage with Wheeler Waring’s story, they will come to understand how primary sources can bring further nuance to their understanding of Black history as it pertains to African American women of the time.

Dox Thrash was born in rural Griffin, Georgia in 1893 to a family that lived in a former slave cabin. As many did during the Great Migration, Thrash would leave home as a teenager to escape the racial violence and harsh economic conditions of the South, as well as seek an education at an art school that would accept Black students. He performed as part of plantation vaudeville-like acts before settling in Chicago. He took night classes at the Art Institute of Chicago while working during the day. After being injured in the first World War, he used his government funding to return to Chicago and enroll full-time at the Art Institute. He would travel for work again and eventually settle in Philadelphia in 1925 to work while pursuing his artistic career. In 1937, after he had completed a Works Progress Administration arts project, he pioneered the carborundum printing technique with two other artists, a process where silicon carbide was used to make etchings on copper plates (Ittmann, 2001). Thrash’s story is representative of the African American experience during the Great Migration. Students choosing to play this track will learn about the conditions that led African Amerians to migrate away from the South and explore issues of class and access for Black artists.

VR and extended reality (XR), an umbrella term for immersive technologies, as tools for education within Black Studies and its related disciplines is hardly new. The “I Am A Man” VR Experience, the Virtual Harlem Project, and Traveling While Black are three examples of XR being used to recreate historical events, spaces, and experiences. While they are all immersive experiences, they differ in the cognitive processes they expect of users. The I Am A Man VR Experience takes users through the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Worker’s Strike and the events leading to the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, aiming to “tap into the emotions of the user” (I Am A Man VR Experience, n.d.). The Virtual Harlem Project was a “virtual representation of Harlem, New York as it existed during the Harlem Renaissance/Jazz Age” (Johnston, n.d.), allowing students an independent means of engaging literature and research on that era. Traveling While Black does not focus on a specific event or space, but instead immerses users in “the long history of restriction of movement for black Americans and the creation of safe spaces in our communities” (Traveling While Black, 2019).

The Virtual Blockson, in contrast to the previous three examples, is a full game. While it does look to recreate spaces and certain events, its primary goal is to simulate the mechanical process of primary source research. Generally, a game, according to game theorists, consists of player actions/decisions, rules (also called strategies), payoff(s) (i.e., rewards or the ability to win/lose), and some aspect of chance or uncertainty (Barron, 2013; Owen, 2013; Prisner, 2014). Similarly, primary source research is also a process where researchers make decisions (i.e., where to research and what to request), with aspects of chance (i.e., they may not find what they are looking for), within set parameters (e.g., time for research, ability to physically visit collections, restrictions on access) that are potentially rewarding (i.e., researchers may find what they were looking for).

In addition to the game, there will be an accompanying teaching toolkit. This toolkit will include guidance on integrating the technology into the classroom, suggestions for integrating the game into curricula, writing prompts and examples of assignments, and information on accessing the game. These materials will all be hosted on a website that will also direct teachers and students to where the game can be accessed for different headsets on different platforms. There will also be instructions for requesting class visits to the immersive Scholars Studio. This immersive studio is a sound proof room with various types of VR headsets and a monitor where the activities of the player can be observed by others in the room. This method of shared interaction has been successful with the K-12 students who tour the space. Classmates often assist and cheer on the peer currently in the headset while watching them play games. This is also important for accessibility for disability. While we will take into account accessibility in the game design, there will be students who will not be able to use the technology (e.g., vertigo can make VR inaccessible for some users). We will also include alternative access recommendations, like using tethered headsets so that students can still observe, to ensure all students can participate.

There has been an ongoing effort to incorporate both immersive VR technologies and computer-based games into the classroom. The expectation is that digital simulations and games will affect users’ presence and positive emotions in learning (Makransky et al., 2015; Senrick, 2013; Watson et al., 2011). For instance, immersive interactions in VR allow users to use their body movement to experience VR content from a first-person perspective. Active bodily involvement helps users gain an embodied understanding of the space, from which emerges a sense of presence (Lindgren et al., 2016; Schubert et al., 1999). Increased spatial presence may help learners to experience narratives presented in a VR movie as if they are directly experiencing them, which in turn may enhance the learning of historical topics.

With this push for an increase in VR and games in history education contexts, there exists a small but growing body of research examining the potentials of these tools in the classroom. Educator and researcher Lee Steven O. Zantua (2017) conducted a quasi-experimental study of sixth-graders’ use of Google Cardboard and Google Expeditions to learn about the seven wonders of the world. VR engagement versus traditional instructional methods was associated with higher mean scores on an objective post-test. In a survey about their VR experience, 95 percent of students agreed or strongly agreed that VR increased their interest in the topic (Zantua, 2017). A larger body of studies, reported primarily in conference proceedings, examined the use of augmented reality, suggesting that interest in interactive and immersive technologies for history education is beginning to grow (Herbst et al., 2008). Similarly, popular historical video games such as Civilization IV and the Assassin’s Creed series “may also help to situate students to more effectively understand the causes and consequences of human choices within historical contexts” (Dow, 2013; Gilbert, 2016; Pagnotti et al., 2012).

Despite the limited empirical investigations into these applications, theoretical discussions of the utility of digital simulations and games in promoting historical education are gaining traction, particularly in publications for K-12 practitioners. These articles posit that using such resources for place-based instruction enables students to interact with sites, artifacts, and perspectives of past peoples in ways that deepen their appreciation for sites’ significance and that promote historical empathy, among other types of historical thinking (Marcus et al., 2017; Sweeney et al., 2018). Exemplar lessons using digital simulations to promote empathy take students’ developmental readiness into consideration (Berson et al., 2018). The development and validation of this project will generate empirical data related to VR and game-based learning in history education and may serve to bolster these calls for their implementation in K-12 classrooms.

As previously mentioned, this game looks to teach the process of primary source research. More specifically, it will adhere to the five learning objectives outlined by the SAA-ACRL/RBMS Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy in 2018:

A. Distinguish primary from secondary sources for a given research question. Demonstrate an understanding of the interrelatedness of primary and secondary sources for research.

B. Articulate what might serve as primary sources for a specific research project within the framework of an academic discipline or area of study.

C. Draw on primary sources to generate and refine research questions.

D. Understand that research is an iterative process and that as primary sources are found and analyzed the research question(s) may change.

In order to complete the game, students will encounter and interact with virtual recreations of primary and secondary sources from the Blockson Collection (i.e., virtual objects). Players must interact with these virtual objects in order to attain information (i.e., clues). As more clues are identified, students will gradually refine the research question they were given at the start of the game and request increasingly specific materials that will help them understand the space within which they have been placed (e.g. starting with secondary reference materials and progressing to more specialized primary and secondary sources in order to understand how these materials differ in content and physical organization). Players will engage in an iterative cycle of using information that has been provided in advance, as well as by the virtual archivist, to identify and request items from the collection that will take them into recreated spaces where they will then identify clues that will redirect them back to the reading room for additional materials. As they examine the sources in the reading room, this will add useful information and annotations to a virtual notebook/tablet that will allow them to return to the recreated Pyramid Club and progress in the game. This information will also refine their research questions. This aspect of the gameplay will replicate the iterative nature of research and show the relationship between primary and secondary sources, as well as how they are used to refine and answer research questions. The materials “pulled” for the player will be in a number of formats, demonstrating the different types of sources that can be applied to different types of research questions.

A. Identify the possible locations of primary sources.

B. Use appropriate, efficient, and effective search strategies in order to locate primary sources. Be familiar with the most common ways primary sources are described, such as catalog records and archival finding aids.

C. Distinguish between catalogs, databases, and other online resources that contain information about sources, versus those that contain digital versions, originals, or copies of the sources themselves.

D. Understand that historical records may never have existed, may not have survived, or may not be collected and/or publicly accessible. Existing records may have been shaped by the selectivity and mediation of individuals such as collectors, archivists, librarians, donors, and/or publishers, potentially limiting the sources available for research.

E. Recognize and understand the policies and procedures that affect access to primary sources, and that these differ across repositories, databases, and collections.

The majority of the above competencies will be supported within the assignments and resources contained within the teaching toolkit. These will include existing resources, typically used to teach undergraduate students how to locate and access materials within a university’s archive and/or special collections, adapted for high school education. These existing resources include handouts and slides associated with Temple University Libraries’ (TUL) information literacy workshops, as well as other materials and practices used by TUL’s Special Collections Research Center (SCRC) for instruction and class visits.1 High school students are regular visitors to TUL and its special collections and often utilize these resources for tours and as part of their research for Philadelphia’s National History Day.2

Additionally, lessons from the Stanford History Education Group’s Reading Like a Historian curriculum will be used to help students develop historical inquiry questions and provide scaffolds for reading and analyzing primary source documents.3 Literature on archival bias, ethics in collecting and repatriation, and descriptive standards will help students think critically about the curation process at play in repositories. These, along with examples of collection policies and visitation guidelines from different repositories will be cited and scaffolded for comprehension by high school students. Some examples include the work of Archives for Black Lives,4 Documenting the Now,5 and others associated with community archiving work and fighting the biases that can be inherent in archival collections. In-person processes like signing in upon arrival, requesting materials, and other basic functions are simulated as part of gameplay.

A. Examine a primary source, which may require the ability to read a particular script, font, or language, to understand or operate a particular technology, or to comprehend vocabulary, syntax, and communication norms of the time period and location where the source was created.

B. Identify and communicate information found in primary sources, including summarizing the content of the source and identifying and reporting key components such as how it was created, by whom, when, and what it is.

C. Understand that a primary source may exist in a variety of iterations, including excerpts, transcriptions, and translations, due to publication, copying, and other transformations.

Within the game, players will encounter virtual recreations of various types of materials. The objective of the game is to contextualize those materials within the larger historical narrative and refine and answer a research question. These materials will consist of related mixtures of primary and secondary sources that show how secondary sources may contain alternative formats of primary sources, or that there are various versions and formats of primary sources (e.g., folders containing both typed transcripts of hand-written correspondence alongside the original correspondence). This is easily achieved due to the multimodal nature of the Blockson Collection’s holdings. Photos, manuscripts, musical recordings, reference materials, and museum objects are all present within the collection. This will give players a better understanding of what constitutes a source. As they encounter materials from the Blockson Collection, they will be able to acquire clues (i.e., annotations) from those sources and see how they apply to the historical focus of that game level. Those clues will act as an example of how the content of a source can be summarized and applied. Skills listed in point “B” will be further developed by prompts within the teaching materials as students are expected to think about key reporting components when assessing how different types of sources are used for different types of research.

A. Assess the appropriateness of a primary source for meeting the goals of a specific research or creative project.

B. Critically evaluate the perspective of the creator(s) of a primary source, including tone, subjectivity, and biases, and consider how these relate to the original purpose(s) and audience(s) of the source.

C. Situate a primary source in context by applying knowledge about the time and culture in which it was created; the author or creator; its format, genre, publication history; or related materials in a collection.

D. As part of the analysis of available resources, identify, interrogate, and consider the reasons for silences, gaps, contradictions, or evidence of power relationships in the documentary record and how they impact the research process.

E. Factor physical and material elements into the interpretation of primary sources including the relationship between container (binding, media, or overall physical attributes) and informational content, and the relationship of original sources to physical or digital copies of those sources.

F. Demonstrate historical empathy, curiosity about the past, and appreciation for historical sources and historical actors.

VR is particularly useful in supporting this learning objective. By having students immerse themselves in a recreated historical space, they engage with historical events differently. By converting it into a game, they have a motive (i.e., completing the game with a high ranking) to investigate and explore the people, events, and time period that construct the underlying context behind the archival materials they are encountering. In addition, prompts included within the teaching materials will guide teachers in helping students further interrogate how the events, spaces, people, and time periods they “visited” are functionally represented by the materials they encountered (e.g., whether that representation is accurate, thorough, and representative). Prompts will also interrogate the bias and gaps in the materials themselves. For example, the Pyramid Club did not allow women to be members. Prompts will guide students through thinking about how this would impact the resources they encountered. While all of this will be explored during this prototyping phase, it will be even more greatly achieved once the full game is developed and students see a greater variety of resources and narratives.

A. Examine and synthesize a variety of sources in order to construct, support, or dispute a research argument.

B. Use primary sources in a manner that respects privacy rights and cultural contexts.

C. Cite primary sources in accordance with appropriate citation style guidelines or according to repository practice and preferences (when possible).

D. Adhere to copyright and privacy laws when incorporating primary source information in a research or creative project.

This learning objective will be accomplished by providing players with a basic research question that they will have to answer in order to progress and win the game. They will have to interact with various materials from the Blockson Collection, as well as recreated objects and spaces in order to unlock information that will contribute to the refinement of the provided research questions as the game progresses. Materials from the Blockson Collection will have records within the TUL catalog that the accompanying teaching materials will list. Students will be able to locate the records and learn how to properly cite them, identify rights information, and think through incorporating them in accordance with legal and ethical guidelines. TUL is the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) service hub for the state of Pennsylvania, known as PA Digital. Within this capacity, it regularly offers workshops and resources on copyright. Examples of these resources can be found on the Rights Resources page of the PA Digital site.6 Resources on archival ethics mentioned under the second guideline will contribute to point “B” above.

While the final Virtual Blockson game will be free and open to the public, for this phase of work, we will focus on students from local high schools within Philadelphia. During the 2020-2021 school year, there were 198,645 students enrolled in Philadelphia schools, 52% of whom were Black (Fast Facts, 2022). As is common in many under-funded districts, the School District of Philadelphia has seen a large number of public school closings – 30 since 2012 (Steinberg 2019). As of 2017, there are seven certified, full-time school librarians for all 216 remaining district operated schools with seventeen libraries kept open by volunteers from the West Philadelphia Alliance for Children (Fast Facts, 2022; Graham, 2020; West Philadelphia Alliance for Children, 2021). As a result of these demographic realities, the project will look to formally incorporate a culturally relevant pedagogical framework (Talpade & Talpade, 2020) into the assessment of the next build phase. Research has consistently shown that learning outcomes are impacted, not only by the content of lessons, but by student perception of the creators of sources. This has been shown to be particularly important for Black students and is an important avenue to fully explore, especially since this will be the first time many students have encountered the concept of an archive.

Regarding distribution during this prototyping phase of the project, the game and teaching toolkit will be distributed in a controlled fashion via pre-selected educators and disabled and non-disabled individuals that will be recruited to participate in the assessment process. The game will be hosted on multiple platforms and the teaching toolkit (i.e., curricula materials and onboarding resources for the teachers), 3D models, and other relevant project information will be hosted internally and distributed to participants before being shared to the public website. We will organize small groups of students, accompanied by their parent(s) or legal guardian(s), to play the game in the Scholars Studio immersive studio for user testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More.

Assessment of Toolkit. We will collect feedback from the teachers selected to participate in this initial rollout. These teachers will be recruited based on the type of school at which they teach, their level of experience with technology, their level of experience in implementing new technologies into a classroom, and the alignment between their curricula and the content of the game. Other considerations, including the demographics of their students, will be weighed accordingly. Fifteen teachers will be selected to peer review the materials in the toolkit. We will ask teachers to independently read and comment on the toolkit. Feedback will then be gathered through a focus group with the teachers. We seek to assess the ease of integration of the toolkit into existing lessons, grade level appropriateness, alignment with SDP curricula and Pennsylvania state standards, and overall usefulness. Participating teachers will receive honoraria for their time.

Accessibility Testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More. The accessibility of the game will be tested on an iterative basis as we develop specific design approaches. These approaches will need to be tested before being fully integrated into the game. Players with motor, hearing, visual, neurological, and intellectual disabilities will need to be brought in to assess whether or not they can physically operate the game, whether they can perceive and respond to sensory cues, whether those with neurological disabilities are safe as those with epilepsy and vertigo are examples of safety concerns, and whether there are enough allowances for those with neurological and intellectual disabilities to enable gameplay (e.g., the ability to pause and resume, making sure text is at a primary reading level). The first six months of the second year of project development will focus on iterative testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More and feedback. Three students from each category of disability will be selected to participate, totalling fifteen students. They will be brought in twice during the iterative phase to test portions of the game, then test them again after their feedback is incorporated. At the beginning of the last six months, they will be brought in to test the overall prototype. We will collect feedback in one-hour sessions with preselected activities and assessment tools so that bugs and accessibility barriers can be identified and corrected. Accessibility testers will receive an honorarium.

Users Testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More for General Gameplay and Pedagogical Efficacy. We will test the playability of the game and its pedagogical efficacy in the last six months of the grant period. During this time, we will work with the teachers to solicit high school students from their classes for participation in user testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More. Teachers will reach out to parents for consent and an invitation to attend their child’s user testingverb gerund or present participle: testing take measures to check the quality, performance, or reliability of (something), especially before putting it into widespread use or practice. “this range has not been tested on… More session. Sixteen students will be selected for participation and divided into two groups that will participate in sessions on two different days. While it would be ideal to test the game in classrooms, at this stage the game will only be a prototype. Our immediate goal is to assess the usability of the prototype and identify any bugs in the gameplay. As a result, students will visit the library with their parents or legal guardians, and be invited into the Scholar Studio’s immersive studio to play the game. Different students will test different types of headsets. This will allow us to test for bugs on different platforms. An hour will be dedicated to gameplay (i.e., getting students in the headsets, letting them play, then getting them out of headsets) and another hour for feedback and assessment. Feedback will be collected via focus group where the students will be gathered together and asked a specified set of questions to assess levels of engagement and enjoyment during gameplay, as well as assessing for comprehension of the themes, events, and specific learning objectives. Responses will be coded and feedback and identified bugs will be addressed. Students will receive a small honorarium for their participation.

While mentioned briefly, the emphasis on Sankofa teaching as a leading principle in this work is essential to our mission. Sankofa is an Akan word meaning “it is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind” (Carter G. Woodson Center, 2017). Erasure of Black history is an ongoing battle and it is evermore important that agency be given to Black students so that they may protect what is at risk of being forgotten. The Virtual Blockson does not aim to tell players a story; it aims to teach them how to write one and how to understand the tales they have already been told. By immersing students in a space without traditional physical and temporal limitations, the Virtual Blockson invites them to examine their history and world from new perspectives that will be crucial to them in the current political and social climate. It is also important to remember that, while virtual reality is an interesting medium with plenty of potential for the future, it is still just a tool that depends on the imagination and will of those who wield it. This can be easy to forget with the technocratic craze of American start-up culture characterized by hyper-wealthy, white men like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Jeff Bezos who make technology appear to be a neutral, self-driving force that only produces progress and profit. However, despite the obsession with profit and neo-liberal ideas of social progress, spaces and tools that center knowledge, play, collaboration, and self-actualization have always existed in the analog and can exist in the emerging digital future. As players engage with the Virtual Blockson, it is our hope they begin to imagine what that alternate digital future can be.

(May 2023)

Barron, E. N. (2013). Game theory: An introduction.

Barton, Keith and Linda Levstik. Teaching History for the Common Good. New York, NY: Routledge, 2004.

Carter G. Woodson Center. (2017, November 20). The power of sankofa: Know history. Berea College. Retrieved from https://www.berea.edu/cgwc/the-power-of-sankofa/.

Berson, I., Berson, M., Carnes, A., & Wiedeman, C. (2018). Excursion into empathy: Exploring prejudice with virtual reality. Social Education 82(2), 96–100.

Brigham, D. R. (2008). Breaking the “Chain of Segregation” the Pyramid Club Annual Exhibitions. The International Review of African American Art, 22(1), 3–17.

Dow, D.N. (2013). Historical veneers: Anachronism, simulation, and art history in Assassin’s Creed II. In M.W. Kapell & A.B. Elliott (Eds.) Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history (pp. 215-239). Bloomsbury.

Downey, Matthew and Kelly Long. Teaching for Historical Literacy: Building Knowledge in the History Classroom. New York, NY: Routledge, 2016.

Fast facts. The School District of Philadelphia. (2022, February). Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.philasd.org/fast-facts/.

Gilbert, L. (2016). “The past is your playground”: The challenges and possibilities of Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate for social education. Theory & Research in Social Education, 45(1), 145-155.

Graham, K. A. (2020, Jan 24). Philly’s got the worst school librarian ratio in the U.S. This group is protesting. TCA Regional News http://libproxy.temple.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/wire-feeds/philly-s-got-worst-school-librarian-ratio-u-this/docview/2344265647/se-2?accountid=14270.

Herbst, I., Braun, A.-K., McCall, R., Broll, W. (2008). TimeWarp: Interactive time travel with a mobile mixed reality game. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Human Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services. Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2-5 September 2008. New York: ACM Press, 235-244.

I Am A Man VR. I AM A MAN. (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2022, from http://iamamanvr.logicgrip.com/

Ittmann, J. W., Philadelphia Museum of Art., & Terra Museum of American Art. (2001). Dox Thrash: An African American master printmaker rediscovered. Philadelphia, PA: Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Johnston, J. (n.d.). Virtual Harlem. An Archive for Virtual Harlem. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://scalar.usc.edu/works/harlem-renaissance/index.

Kirschke, A. H. (2014). Laura Wheeler Waring and the women illustrators of the Harlem Renaissance. In Kirschke, A. H. (Ed.), Women artists of the harlem renaissance. (pp. 85-114). University Press of Mississippi.

West Philadelphia Alliance for Children. Library opening and staffing. (2021, July 9). Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://wepac.org/library-opening-and-staffing/.

Lindgren, R., Tscholl, M., Wang, S., & Johnson, E. (2016). Enhancing learning and engagement through embodied interaction within a mixed reality simulation. Computers & Education, 95, 174-187.

Makransky, G., & Lilleholt, L. (2018). A structural equation modeling investigation of the emotional value of immersive virtual reality in education. Educational Technology Research and Development, 66(5), 1141-1164.

Marcus, A., Stoddard, J., & Woodward, W.W. (2017). Teaching history with museums: Strategies for K-12 social studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). (2013). The college, career, and civic life (C3) framework for social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K-12 civics, economics, geography, and history. Silver Springs, MD: NCSS. Retrieved at: https://www.wscss.org/c3framework#:~:text=The%20C3%20Framework%20is%20an%20inquiry%20approach%20to%20teaching%20studies.&text=C3%20IS%20a%20framework%20for,go%20through%20the%20investigative%20process.

Nokes, Jeffery and Susan De La Paz. “Writing and Argumentation in History Education.” In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by Scott Alan Metzger and Lauren McArthur Harris, 551-578. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

Owen, G. (2013). Game theory. Emerald Publishing Limited.

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. (2021, December). Laura Wheeler Waring: Her Best Face Forward. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ltK486TaGY&ab_channel=PennsylvaniaAcademyoftheFineArts%28PAFA%29.

Pagnotti, J., & Russell, W.B., III. (2012). Using Civilization IV to engage students in world history content. The Social Studies, 103(1), 39-48.

Prisner, E. (2014). Game theory: Through examples.

Reisman, Abby and Sarah McGrew. “Reading in History Education: Text, Sources, and Evidence.” In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by Scott Alan Metzger and Lauren McArthur Harris, 529-550. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

SAA-ACRL/RBMS Joint Task Force on the Development of Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy. Guidelines for Primary Source Literacy. Society of American Archivists, 2018, https://www2.archivists.org/sites/all/files/Guidelines%20for%20Primary%20Souce%20Literacy_AsApproved062018_1.pdf.

Schubert, T., Friedmann, F., & Regenbrecht, H. (1999). Embodied presence in virtual environments. In Visual representations and interpretations (pp. 269-278). Springer.

Senrick, S. (2013). Civilization IV in 7th grade social studies: Motivating and enriching student learning with constructivism, content standards, and 21st century skills. In Y. Baek & N. Whitton (Eds.), Cases on digital game-based learning: Methods, models, and strategies (pp. 82-96). IGI Global; Watson

Sexias, Peter and Tom Morton. The Big Six: Historical Thinking Concepts. Toronto, Canada: Nelson, 2013.

Steinberg, Matthew P., MacDonald, John M. (2019, April) “The effects of closing urban schools on students’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Evidence from Philadelphia.” Economics of Education Review, 69, pp. 25-60. ScienceDirect, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.12.005.

Stoddard, Jeremy. “Learning History Beyond School: Museums, Public Sites, and Informal Education.” In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by Scott Alan Metzger and Lauren McArthur Harris, 631-656. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2018.

Sweeney, S. K., Newbill, P., Ogle, T., & Terry, K. (2018). Using augmented reality and virtual environments in historic places to scaffold historical empathy. TechTrends, 62(1), 114-118.

Talpade, M. &Talpade, S. (2020, January). Sankofa Scale Validation: Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, Racial Identity, Academic Confidence, and Success. Journal of Instructional Pedagogies, 23.

Temple University Libraries. (n.d.). John W. Mosley Photographs. Temple Digital Collections. https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll17.

Traveling while black on oculus go. Oculus. (2019). Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.oculus.com/experiences/go/1994117610669719/.

VanSledright, Bruce. Assessing Historical Thinking & Understanding: Innovative Designs for New Standards. New York, NY: Routledge, 2014.

Watson, W.R., Mong, C.J., & Harris, C.A. (2011). A case study in the in-class use of a video game for teaching high school history. Computers & Education, 56(2), 466-474.

Wineburg, Sam. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2001.

Wineburg, Sam, Daisy Martin, and Chauncey Monte-Sano. Reading Like a Historian: Teaching Literacy in Middle & High School History Classrooms. New York, NY: Teachers College Press, 2013.

Wright-Maley, C., Lee, J.K., & Friedman, A. (2018). Digital simulations and games in history education. In S.A. Metzger & L.A. Harris (Eds.) The Wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning (pp. 603-629). Wiley Blackwell.

Zantua, L.S.O. (2017). Utilization of virtual reality content in grade 6 social studies using affordable virtual reality technology. Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 5(2), 1-10.

We welcome and encourage your comments. You must create a free account to participate.

CLIR is an independent, nonprofit organization that forges strategies to enhance research, teaching, and learning environments in collaboration with libraries, cultural institutions, and communities of higher learning.

Unless otherwise indicated, content on this site is available for re-use under CC BY 4.0 License